Ultra-Thin Watchmaking Part II: A Modern History Of Thin Elegance, And The Birth Era Of Extremes

Part 2 picks up with the Caliber 21 and the golden age of thin movements, then fast-forwards to today’s record-breaking novelties. Is this still watchmaking or just engineering gymnastics?

In Part 1 of the story of ultra-thin watchmaking, we examined how technical acumen and fashion trends converged to push the world toward thin, accurate watches. The English dandy sensibility of Beau Brummell fused with the French watchmaking prowess of Lepine, made the thin watch a beacon of refinement, a signal of aristocracy that eventually trickled down and was democratized for the rest of us plebs.

But at the turn of the 21st century, something shifted. The pendulum of style and modern mechanical innovation swung hard, and thinness stopped being about elegance or refinement. It became a flex, a signal of technical achievement. The pursuit of the thinnest possible watch started to feel less like a cohesive exercise in design and more like a stunt, a marketing exercise to prove what a company could “get away with” rather than to make a complete product for the consumer.

When you prioritize thinness above all else, you lose the heart and soul of the timepiece. It becomes a whimsical de jure exercise, not a de facto expression of refinement. When thinness becomes the goal instead of a byproduct of good design, the result may impress on spec sheets, but it lacks soul. The original purpose of creating an elegant dress watch for life’s elevated moments, to slip quietly under the cuff, was ushered out the door, replaced by competition, bragging rights, and chest-thumping grandeur.

And I’m not entirely sure if that’s wrong. Technical advancement for its own sake is still advancement. It’s still innovation. Should the motivation behind it matter? I’m honestly not sure.

But it does seem that modern ultra-thin watchmaking has lost sight of its own history. Once, it was about creating a unified, wearable piece of horology, something to be appreciated and enjoyed on the wrist. Today, too often, it feels like a modern flex.

So how did we get here? How did we go from Lepine and Brummell to the ThinKing?

The F. Piguet Caliber 21

For anyone who follows watches, the name Piguet should be anything but unfamiliar. The family has long reigned as one of the great dynasties in the Vallée de Joux. In 1858, Louis-Elisée Piguet founded what would later become Frédéric Piguet in Le Brassus, setting off a domino effect in high-end movement manufacturing that shaped the next century. In 1925, his son Henri-Louis Piguet cemented the family’s legacy with the creation of the caliber 21. Originally dubbed the caliber 99, the ultra-thin movement was a passion project Henri-Louis worked on for 15 years. The final version, still called the caliber 99 at the time, measured just 1.69mm thick, with a 20.4mm diameter, 18 jewels, a 2.5 Hz beat rate, and a 42-hour power reserve.

One of the defining features shared by most ultra-thin watch movements is the use of a “hanging barrel.” This design means the barrel and ratchet wheels are supported only from one side, eliminating the upper movement bridge traditionally used to hold the crown and ratchet wheels in place (the ratchet wheel being the one that sits atop the mainspring barrel). While this approach is essential for reducing overall thickness, it does compromise structural rigidity, increasing the risk of uneven wear over time, since all the mainspring barrel load is concentrated on a single pivot.

In 1955, after some key upgrades, including a redesigned escapement beating at 3 Hz, revised bridges, and the addition of (much needed) shock protection, the movement was renamed the caliber 21. These modifications increased the thickness slightly to 1.73mm, but the trade-off was worth it. The caliber 21 would go on to hold the title of the world’s thinnest wristwatch movement for nearly two decades.

Like Jaeger-LeCoultre’s ultra-thin calibers, it was widely adopted by many of the top manufacturers in Swiss watchmaking. The caliber 21 served as the base model for the Patek Philippe calibers 175,177, Rolex caliber 650, IWC caliber 171, Omega caliber 700, the Zenith caliber 53.5 and many others. Essentially all of the following calibers that I discuss in this story were based on the caliber 21 in some form or fashion.

The mid-1950s, when the caliber 21 cemented its legacy, were truly a golden era for ultra-thin mechanical watchmaking. JLC’s caliber 803 launched in 1953. Vacheron Constantin’s caliber 1003 followed in 1955, and Piaget threw their hat in the ring in 1957 with the caliber 9P. These foundational movements would lay the groundwork for future icons like the caliber 920 and caliber 849.

And the story of these ultra-thin calibers are not just tales of the past. The use of these ultra-thin calibers lives on. Just this past March, Ming released a series of 10 limited editions under the name Project 21, each powered by a NOS caliber 21.

Ultra-Thin Vacheron Constantin “Knife” Pocket Watch, 1931

As stated previously, the history of horology is anything but chronological or linear. So while the story of the caliber 21 begins in 1925 and truly comes into its own by 1955, we now need to rewind the clock once again to explore a pivotal chapter in the evolution of ultra-thin watchmaking.

By the early years of the Great Depression, wristwatches had officially “arrived” in the mainstream consumer market. One famous early example of a watch deliberately designed for the wrist dates to 1810, when Queen Caroline Murat of Naples (Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister) commissioned Abraham-Louis Breguet to create one. (A side note to this is that “bracelet watches” technically predate Breguet with Queen Elizabeth I having been gifted one in 1571 — again history is a sticky subject). Completed and delivered in 1812, the oval-shaped timepiece No. 2639 in Breguet’s archives featured a silvered dial with Arabic numerals, a chiming repeater, and a bracelet woven from hair and fine gold threads. Unfortunately, it has allegedly been lost to history.

Fast forward a century, and we can’t forget the Cartier Santos-Dumont, designed in 1904 and released to the public in 1911, but for the most part, wristwatches weren’t widely embraced until soldiers trudging through the trenches of the Western Front needed them. Wristwatches began to seriously challenge pocket watches post-war, but the pocket watch remained a focus of artistry. Which brings us back to 1931, and Vacheron Constantin unveiling their so-called “knife” pocket watch, ref. 10726.

“Knife” watches were a collective term for any ultra-thin watch during this time and Vacheron Constantin arguably made the best. However, Jaeger-LeCoulture’s caliber 145 from 1907 measuring 1.38mm was nothing to thumb your nose at, and it was the predecessor of some of JLC’s most famous ultra thin wristwatch movements. But the Vacheron Constantin reference 10726 from 1931 housed a movement just 0.90mm thick. To put that in perspective, that’s about the thickness of a heavy credit card, nine sheets of standard printer paper stacked together, or a guitar pick if music is your thing. As Jack once noted, “Only three were made for obvious reasons; this was not exactly a go-to mechanism in terms of reliability but as far as I know nobody has ever made anything thinner (again, for pretty obvious reasons).”

This wasn’t a watch for the everyday man. It was the kind of piece that would disappear seamlessly into the breast pocket of a perfectly tailored suit, an exercise in refinement, flamboyance and the epitome of ultra-thin watchmaking being pushed to its very limits.

The Caliber 1003 and the Lesalle 1200

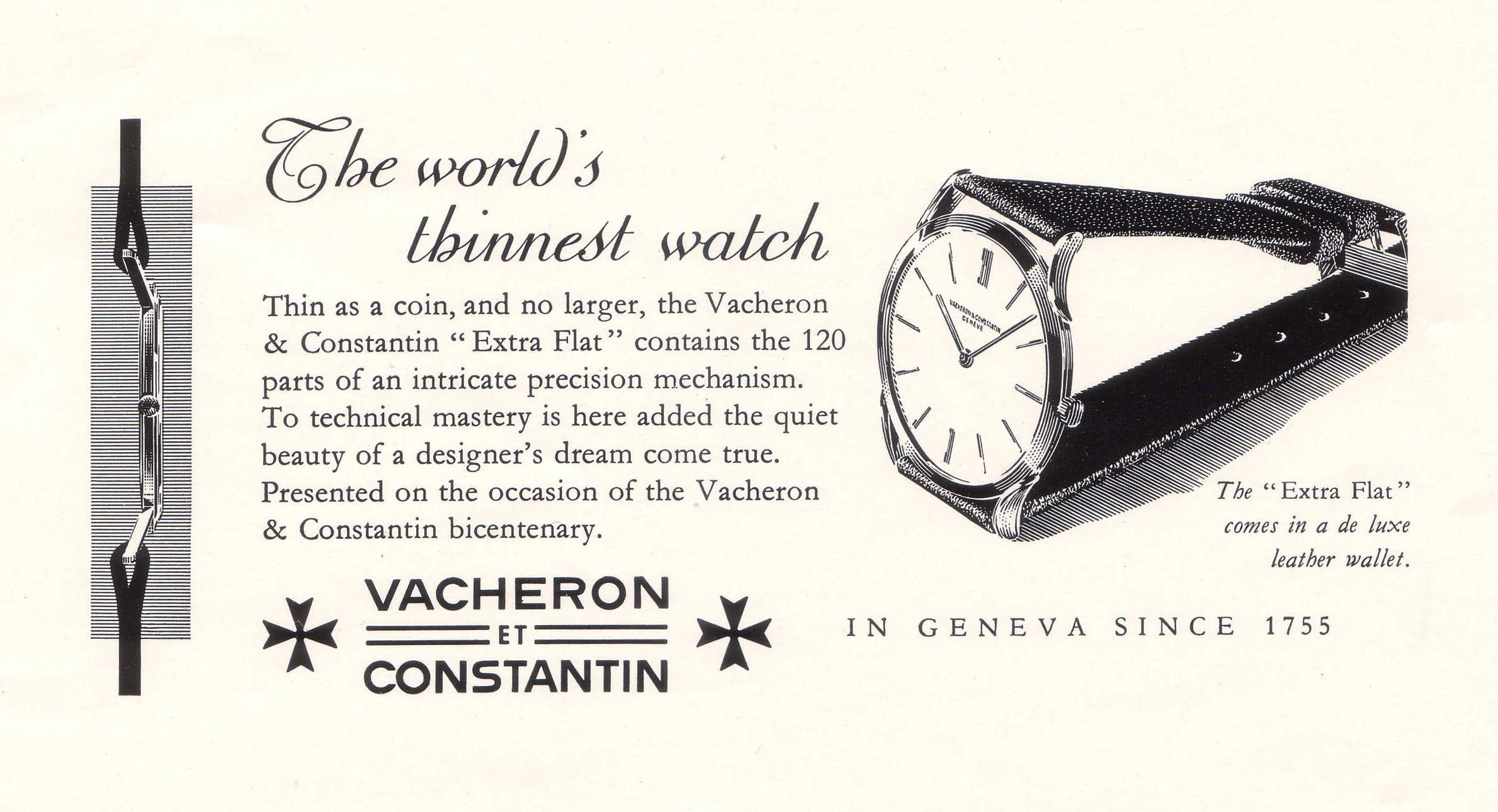

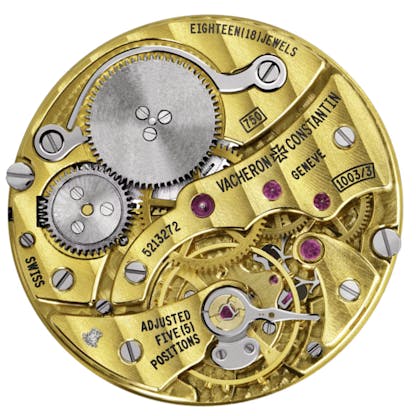

In 1955, Vacheron Constantin ran an ad calling one of their watches “la montre la plus plate du monde” translated as “the flattest watch in the world.” Inside was the legendary caliber 1003. This full-bridge, hand-wound movement stood just 1.64mm tall and remained the benchmark for ultra-thin watchmaking for more than 60 years.

What makes it even more remarkable is that it was originally found in only one watch: the 1955 Ultra-Flat (although there are some who call it the Ultra-Thin and even the Ultra-Fine). When it was reissued in 2010, it was renamed the Historiques Ultra-Fine 1955, and incredibly, sans the display caseback of the modern edition, it was essentially the same watch. Same caliber 1003 ticking away inside holding on to its legendary status.

However, to call early-to mid-20th-century under-the-dial watchmaking “complicated” would be selling it short. The truth is, despite Vacheron Constantin proudly claiming this watch as their own, the credit for the movement goes to the watchmakers at Jaeger-LeCoultre.

In 1953, JLC introduced the caliber 803, later to be named VC caliber 1003. But as you can see in the photo below, aside from a few cosmetic differences, the movements are virtually identical. You don’t need to be a trained watchmaker to spot it. In the post–World War II years, Vacheron had an extremely close relationship with JLC, who supplied many ebauches.

I highlight this movement not just for its history, but also because its modern counterparts represent some of the finest ultra-thin watchmaking ever produced. And while many of Vacheron’s ultra-thin calibers came straight from JLC, Jaeger-LeCoultre curiously didn’t use many of them in their own watches, so you’ve got to give credit where credit is due.

And Vacheron wasn’t the only one taking advantage of JLC’s expertise; Audemars Piguet’s legendary caliber 2003 is, for all intents and purposes, the same as JLC’s 803 aka VC 1003.

Here’s the kicker (and I say this with a wink to anyone who claims refined taste): the caliber 1003 isn’t even the thinnest movement Vacheron Constantin ever used. That record belongs to a caliber most people have probably never heard of.

Enter the Lassale caliber 1200. Produced for only a few short years starting in 1976 by the little-known Bouchet-Lassale SA, this movement was an astonishing 1.2mm thick. It pulled this off by ditching traditional bridges altogether, instead mounting the entire gear train on ball bearings set directly into the mainplate.

Now, ball bearings in the going train are generally frowned upon when it comes to long-term reliability (they can produce unwanted power variations) but at the time this was a groundbreaking design. I can see the Guinness ad now, shouting “Brilliant!” and you’ve got the vibe. The big downside? These movements were essentially unserviceable. If something went wrong, you didn’t repair it, you had to swap it out for an entirely new movement. Think of it like replacing your MoonSwatch movement… except this was a finely finished mechanical caliber worth thousands of dollars.

Vacheron Constantin’s version, known as the caliber 1160, at least dressed things up with haute finishing, including Geneva stripes.

As for how the rights to these movements changed hands, well, that history is its own confusing jigsaw puzzle. But from what I can gather, the Lassale caliber 1200 was originally reserved exclusively for Piaget as long as it remained independent. Once Piaget came under Cartier’s ownership, that exclusivity ended, and Nouvelle Lemania SA (which had acquired Lassale’s movement catalog) was free to supply the caliber to other watchmakers, including Vacheron Constantin, hence the caliber 1160.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre Caliber 920

Between the caliber 803 (1953) caliber 1003 and 21 (1955), the caliber 839 (1975) and the caliber 1200 (1976), there was one movement to rule them all (to borrow a little Gandalf energy): the caliber 920, launched in 1967.

Wei Koh of Revolution put it best, “The Jaeger-LeCoultre Calibre 920 is the most significant automatic, ultra-thin calibre ever created for several reasons. The first is that without it, two of the world’s most important watches. The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak reference 5402ST from 1972 and the Patek Philippe Nautilus reference 3700/1A launched in 1976 would not have been possible.” He continued, “Second, the Calibre 920 can be considered one of the most important factors in Audemars Piguet’s success over the past half-century. Not only did it power the legendary Royal Oak, but it also made possible the watch that truly saved Audemars Piguet from the Quartz Crisis.”

What makes the 920 even more fascinating is that Jaeger-LeCoultre, the company that designed and built it, again, never used it in their own watches. Instead, JLC supplied it as an ébauche to the three maisons often referred to as watchmaking’s “Holy Trinity”: Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Vacheron Constantin (in the famed 222). Each brand received the movement in kit form and finished it in their own style.

To be a bit more concise, the caliber 920 is something of a chameleon. It goes by many different names depending on which of the “Holy Trinity” brands used it. Over the last 40+ years, it has quietly powered foundational automatic models from Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Vacheron Constantin. Patek’s versions carried the designations 28‑255 and 28‑255 C. At Vacheron Constantin, it appeared as the 1120, 1121, and 1122. And for Audemars Piguet, it became the 2120, 2121, and 2122. Whatever the name, it’s the same legendary ultra‑thin engine underpinning some of the most iconic watches ever made.

Walt Odets, the godfather of technical watch writing, once called the Caliber 920 “inarguably the most beautiful wristwatch movement ever produced.” Jack (you know which one) has even called it one of his all-time favorites, alongside the Caliber 849, which we’ll get to shortly.

To this day, the Caliber 920 remains the thinnest full-rotor automatic movement ever made. There are slimmer automatics, like Patek Philippe’s micro-rotor Caliber 240 or Bulgari’s BVL 138 or peripheral-rotor designs like Bulgari’s BVL 288 automatic tourbillon. But those movements achieve their thinness by altering the rotor system.

In its simplest no-date configuration, it measures just 2.45mm tall. Add a date complication, as seen in the versions used by Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe, and it rises to 3.05mm.

As stated previously, the irony of this movement is of course that JLC never used its own creation. Imagine Beethoven composing Symphony No. 5 and never performing it himself? There’s simply no real comparison in terms of an ultra-thin movement that changed the trajectory of watchmaking.

This movement’s résumé is staggering and speaks for itself. But for me, the greatest execution of the Caliber 920 is found in the Vacheron Constantin Caliber 1120, used in the now-discontinued Overseas Ultra-Thin unveiled at SIHH 2016. It might just be my personal grail … if I believed in such a thing.

Piaget Caliber 9P and Caliber 12P

Throughout this look at modern thin mechanical watchmaking, there’s one name I’ve deliberately kept on the sidelines, not out of neglect, but because they deserve their own spotlight. While Jaeger-LeCoultre will always, in my book, wear the crown of ultra-thin movement making, Piaget has earned its moment in the sun. With over 25 calibers qualifying as ultra-thin to their credit, Piaget may not be discussed as often in collector circles for their movements as they are for their distinctive case shapes, hard stone dials, and unabashedly “geezer” aesthetic flourishes. But make no mistake that Piaget is a master of thinness in its own right. At the summit of their mechanical movement legacy stand two references: the 9P and the 12P. (And yes, I’m grateful for their mercifully simple naming system.)

The 9P debuted in 1957, right in the heart of the golden era for ultra-thin watchmaking, measuring just 2mm thick. It featured 18 jewels, a 36-hour power reserve, a beat rate of 19,800 vph, and a diameter of 20.5mm. It was a pure two-hand movement, designed, developed, and produced entirely in-house at a time when few brands could make that claim. The watch housing it would later evolve into what we now know as the Altiplano, a model line that remains central to Piaget’s catalog.

Three years later, in 1960, Piaget introduced the 12P. Measuring just 2.3mm thick, it was the thinnest automatic watch in the world at the time. The technical execution was uncompromising. Though only partially visible beneath the balance wheel, the main plate was fully decorated with circular graining, while the bridges displayed vertical côtes de Genève and hand-chamfered edges. Instead of a traditional central rotor, the 12P used an off-center micro-rotor placed so far toward the edge that it extended beyond the perimeter of the base plate.

This design required cases to be discreetly hollowed out inside, allowing the rotor the freedom to spin. And in true Piaget fashion, the rotor itself wasn’t just a functional component, it was crafted entirely from solid 24-karat gold, combining the necessary mass for efficient winding.

The modern history of ultra-thin watchmaking can’t be told without Piaget. They’ve carried that tradition forward to this day, trading records and innovations with the biggest watch houses in the world. But what makes their achievements feel especially meaningful is that these creations are entirely their own.

An Anecdote: Jaeger-LeCoultre Caliber 849

Despite Jaeger-LeCoultre never using the Caliber 920 in its own watches, the brand did have its own ultra-thin hero: the Caliber 849. Used in the JLC Master Ultra-Thin (now discontinued) and also in a rare IWC Portofino, it debuted in 1994, the same year, for reasons I can’t explain, that Hollywood decided to release every great movie of the ’90s, including a string of Jim Carrey classics that someone will inevitably make a Netflix documentary about one day.

Originally introduced as the 839 in 1975, the 849 is a hand-wound movement that, at just 1.85mm thick, claimed the title of the world’s thinnest traditional movement (semantics are funny). In many ways, it’s a sibling to Vacheron Constantin’s Caliber 1003. But “sibling” is doing a lot of work here while the architecture is related, there are clear differences in finishing, materials, and some key technical details.

You might be wondering, as I did, that if one is thinner than the other, can they really be considered the same movement? Is this collaboration, or creative theft? The truth is a little messy, and labeling it “complicated” seems to fit the bill in describing this relationship.

To shave down the height, JLC followed a classic playbook for reducing height. This includes the use of a hanging mainspring barrel, as well as a balance with steps on the arms to allow it to sit closer to the movement plate. JLC also changed the position of the impulse jewel, which in the 849 is on the underside of one of the balance arms (instead of on an impulse roller)..

When it comes to traditionally constructed, hand-wound movements (automatic calibers will always be thicker thanks to their rotors, at least in the case of full rotor automatics) the caliber 849 pretty much grazes the practical limit of thinness for a wristwatch movement intended to be a daily runner. Yet, unlike some modern record-chasing thin movements, it doesn’t feel like a stunt.

Place it beside the 1003 or the 920, and it stands with equal grace, proof that classical movement design, done right, can still stir something in you. It is cool because it moves you and comes from a time when it wasn’t about eyeballs, but about accomplishing something incredible for the greater good of humanity. (Maybe that is a bit too dramatic).

The Modern Race For Thin

This brings us to today. The modern race for thinness has pushed watchmaking to its most extreme frontiers. At the very top of this razor‑slim hierarchy is the Konstantin Chaykin ThinKing, a 2024 prototype that measures 1.65 mm. It isn’t a commercial piece. It comes across as more of a statement of mechanical audacity and hammered at Phillips this past year for 508,000 CHF.

Just behind it sits the Bulgari Octo Finissimo Ultra COSC, also another 2024 release, which holds the record for the thinnest production watch (semantics again) at 1.70 mm. Powered by the BVL 180 caliber and built from titanium and tungsten carbide. It is COSC certified (as the name suggests) which is quite impressive, and possibly makes it a bit more wearable than the ThinKing, although I suppose that is up to the wearer.

In third place is the Richard Mille RM UP‑01 Ferrari, released in 2022 at 1.75 mm thick. This guy measures 1.75 mm with an integrated movement able to withstand 5,000 g’s of shock. Unsure why it can withstand that many g’s but still impressive.

Then there’s my personal favorite Piaget, the house that has been synonymous with ultra‑thin for over half a century. Its Altiplano Ultimate Concept Tourbillon, unveiled in 2024 for the brand’s 150th anniversary, measures 2.00 mm, making it the thinnest tourbillon wristwatch ever created. Every element from the case, movement, and even the tourbillon itself is integrated into a single, seemingly impossible sleek structure. Alongside it stands the time‑only Altiplano Ultimate Concept, which first appeared as a prototype in 2018 and entered production in 2020, also coming in at 2.00 mm.

Together, these watches illustrate the modern philosophy of ultra‑thin horology. Once, thin watches were about elegance and refinement, a quiet expression of taste. Today, the race for thinness has become an arena for technical one‑upmanship, a test of which brand can bend physics the farthest without breaking it. The ThinKing may hold the current title, but every one of these pieces is a marker in the ongoing story of how far and how flat mechanical watchmaking can go.