Chains Of Precision: Rediscovering Why The Fusée & Chain Mechanism Is Used In Modern Watchmaking

The fusée and chain is a centuries-old solution to timekeeping’s oldest challenge.

It was through the discovery of the Richard Lange “Pour le Mérite” that I first learned about the fusée and chain mechanism. A few years back, I was sifting through our inventory when I came across the reference 260.028. Through the caseback at the twelve-o’clock position, I noticed a small, bike-like chain—something I’d never before encountered in a movement .

I’ve said it before and will say it again: “Watches are a game of details.” But every so often, a stroke of serendipity or a spark of curiosity leads you to a detail that sets you on a new path. That tiny chain, visible through the aperture, launched me on a technical journey to understand a long-overlooked solution to one of watchmaking’s greatest challenges.

The fusée and chain transmission represents one of the oldest and most effective solutions in horology for addressing the inconsistencies in a mainspring’s power output. Originating centuries ago in clockmaking, this intricate mechanism has evolved to have a rare but respected place in modern wristwatches, where it showcases both engineering prowess and adherence to horological tradition.

Brief History of the Fusée and Chain

The term “fusée,” as you might have guessed, is French, meaning “spindle full of thread.” However, beyond that little factoid, the origin of the fusée is not as clear. Many credit clockmaker Jacob Zech of Prague for being the first to use the mechanism in a clock in 1525, around the same time the first spring-driven clocks appeared. However, the concept of the fusée likely didn’t originate with clockmakers; the oldest known example appears in a crossbow windlass depicted in a 1405 military manuscript.

Additionally, 15th-century drawings by Filippo Brunelleschi and Leonardo da Vinci illustrate fusees. The oldest surviving fusee clock, also the earliest spring-driven timekeeper, is the “Burgundy Clock” or Burgunderuhr, a chamber clock adorned with imagery hinting it was created around 1430 for Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy.

It could be 1430, it could be 1525 — all depends on who you ask, or whatever the recent update on Wikipedia states, as per most of history.

In the 15th century, springs were introduced to power clocks, enabling the creation of smaller designs. However, these early spring-driven clocks were notably less precise than their weight-driven counterparts. While a suspended weight provides a steady force to drive the clock’s gears, the force from a spring decreases as it unwinds. This led to smaller clocks, which was a plus, but also dramatically less accurate.

The verge escapement that was in use at that time and common in early clocks was especially affected by this fluctuation in force, causing spring-driven clocks to gradually slow down as they ran. This issue, known as a lack of isochronism (which is your word of the day), resulted in inaccurate timekeeping.

Understanding the Problem: Uneven Power Delivery

I believe it was Henry Ward Beecher who said, “It’s not revolution that destroys machinery, it’s friction.”

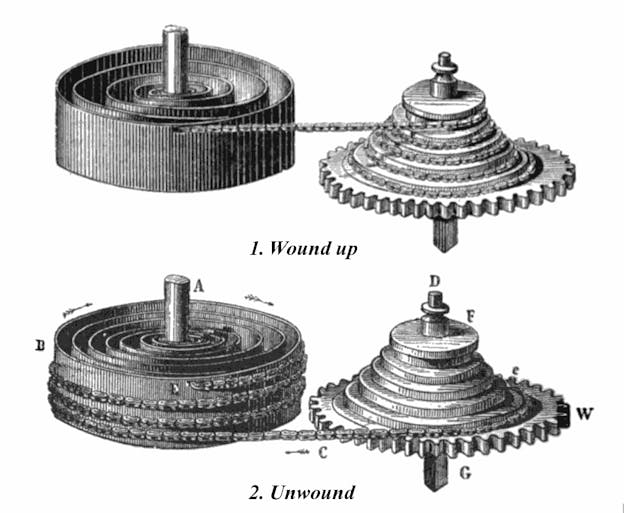

At its core, the fusee and chain system addresses a fundamental issue of the uneven force delivered by the mainspring. When fully wound, the mainspring generates a high level of tension, which diminishes as it unwinds. This fluctuation can disrupt the accuracy of timekeeping, as the regulating mechanism receives varying levels of torque over the duration of the power reserve.

The fusée and chain system combats this by using a cone-shaped fusee and a tiny chain to offset the torque variance, effectively smoothing out the delivery of power.

How the Fusée and Chain System Actually Works

The fusée and chain transmission consists of a helical fusee cone, a chain, and the mainspring barrel. When the watch is fully wound, the chain wraps tightly around the fusée cone. As the spring relaxes (or releases due to the escapement), the barrel rotates, pulling the chain off the fusée in a way that adjusts the force transmission, thereby ensuring a more constant torque.

The shape of the fusée cone enables this balancing act, drawing on principles similar to a pulley or lever system, where the radius (or lever arm) varies to achieve an equilibrium in force.

Close your eyes, well, not literally, otherwise you can’t read this, but figuratively close your eyes. Now imagine you’re pedaling up a hill on a bicycle. At first, you’re feeling strong, so you pedal in a high gear. But as you tire, you’d ideally switch to a lower gear to make pedaling easier and keep moving steadily uphill. The fusée and chain do something similar for your watch. When the mainspring is full of energy (like you at the bottom of the hill), it doesn’t need much help to push the gears. But as it “gets tired” and loses energy, the fusée and chain steps in to provide extra leverage, ensuring that the movement receives a steady push right until the mainspring is out of juice.

Challenges of the Fusée and Chain

While effective at mitigating power inconsistencies, the fusée and chain system is not without its limitations. One of the key challenges with fusée and chain systems is size. Because the mechanism needs space for the cone, chain, and additional gears, watches containing a fusee and chain are often thicker and broader—features that suit certain traditional designs but may not appeal to those who prefer slim and streamlined timepieces.

Historically, this sizing issue largely influenced who adopted the fusee and chain system. English watchmakers historically favored this robust solution, aligning with their preference for durable and substantial movements. By contrast, French watchmakers typically pursued more delicate, refined designs and steered away from the hefty build the fusée and chain required. The French leaned toward elegance and finesse, favoring solutions that allowed for thinner profiles and more intricate cases, avoiding the bulkiness that a fusée and chain brings to the wrist.

Another problem occurs at the extremes of being fully wound or nearly unwound — this is where the fusée-and-chain mechanism encounters limitations. This occurs because, in these states, the mainspring’s torque output changes abruptly and unpredictably. To maintain optimal precision, especially in the case of A. Lange & Sohne, who use this mechanism in five current production models, the power reserve is therefore restricted to the middle range of torque delivery, where the energy output diminishes steadily and predictably.

As well, A. Lange & Sohne implements a blocking mechanism to bypass the sudden loss of force when completely wound. The intent of this blocking system is essentially two-fold. First to lock the ratchet wheel so the chain won’t break due to overwinding. The second is to lock the ratchet wheel to prevent the mainspring from suddenly expanding and violently breaking the chain.

If you look at the image above you can see that a rivet (1) in the chain activates a lever system (2) at whose end an arresting tooth (3) pushes into the ratchet wheel (4). This lever essentially locks the fusée (5), which is connected to the ratchet wheel.

They conversely solved the issue of when the watch is nearly unwound. This mechanism halts the movement just before the mainspring fully unwinds, relying on the power-reserve wheel (6) as the key component.

If you look at the image above you will notice that at the end of this rotation, a lever’s beak (7) drops into a notch in the power-reserve wheel, while the opposite end (8) swings into the path of the blocking finger (9). Attached to the fourth-wheel arbor, this blocking finger rotates once per minute. Within 60 seconds, it contacts the lever and halts the movement entirely.

One of the other details specific to a fusée and chain system is that you need to have a maintaining power system in the fusée cone. When you wind a watch it temporarily disrupts the flow of power from the mainspring to the movement when the chain transfers to the cone.

I know this sounds like slight horological gibberish but I promise it is not. Essentially, when you wind a fusée watch you are pulling the chain off the mainspring barrel and onto the fusée, which interrupts the power transmission. To combat this all fusee and chain watches need a maintaining power system, which is generally built into the design of the cone and ensures the watch continues to run while winding occurs.

Other Solutions

Despite the fusée and chain’s effectiveness, there are still many other solutions to this age-old watchmaking conundrum.

– Constant Force Mechanisms: These systems use a secondary spring or a remontoir d’égalité to release energy in even intervals. Although intricate, these mechanisms are more compact and require less space than a fusee and chain, making them suitable for modern, smaller wristwatches.

– Advanced Materials and Barrel Designs: Advances in materials science have led to mainsprings that are far more consistent in their power output. For instance, silicon components or mainsprings coated with advanced alloys offer improved energy distribution over time.

– Multiple Barrels: Some watches use twin or multiple mainspring barrels, distributing the power over a longer span, which naturally balances the force delivery to the movement.

Each of these options presents a more practical alternative to the bulky fusée and chain.

Why Choose a Watch with a Fusée and Chain?

It is wildly old, not the most effective mechanism to solve for constant force, is tremendously expensive and tedious to service, and forces one to wear a larger watch…So, why would anyone choose a fusée and chain watch today, when better alternatives are readily available?

For one, the mechanism is a marvel of engineering, requiring precision in design and meticulous assembly. Looking at that chain through an open caseback is as much of a pleasure as listening to the sweet sounds of a minute repeater chime in the distance. (I have never felt more like a true watch nerd than when writing that sentence).

It’s also a nod to horological history—a reminder of the creativity early watchmakers used to solve problems. Collectors and enthusiasts often view the fusée and chain as a symbol of craftsmanship and complexity, appreciating it not only for its function but for the historical significance and ingenuity it represents.

Not all fusée and chain watches are the same, but due to their complexity, they tend to stay within the “luxury field” of horology. That said, there are a few standouts excluding the A. Lange & Sohne Richard Lange “Pour le Mérite” ref. 260.028.

The Breguet La Tradition Fusée Tourbillon was launched in 2012 and remains one of my all-time favorite Breguets. There are not many maisons that incorporate a fusée and chain with a tourbillon and Breguet is one of them. I’ll leave that up to you to decide. But in full transparency, I must admit I am not an open-worked dial kind of guy, yet this watch is perfect with it because of that chain.

Another watch that showcases the chain through an aperture on the dial side is the Zenith Academy Georges Favre-Jacot. Coming in at 45mm and 14.35mm, it is not for the weak-wristed. Released in 2014 for the 150th anniversary of Zenith the watch is powered by the El Primero 4810 movement, featuring a high-frequency balance. This elevated oscillation rate demands greater energy, necessitating a larger and more robust mainspring. However, a powerful mainspring introduces its own challenges. The variation in torque between a fully wound and a completely unwound mainspring is substantial, which can lead to issues with isochronism (there is that word again).

The fusée and chain mechanism provides an elegant solution for this watch, effectively stabilizing the power output. This system enables the high-frequency movement to maintain its accuracy across the full extent of its power reserve.

Ultimately, owning a fusée and chain watch is about appreciating a unique approach to a technical challenge—an homage to centuries-old techniques that laid the foundation for modern watchmaking. It’s a choice rooted less in practicality and more in an appreciation for the mechanical beauty and legacy that the fusée and chain represents. This mechanism serves as a tangible link to history, embodying the watchmaker’s pursuit of accuracy and their mastery of both engineering and art.

Frequently Asked Questions About Fusée and Chain Watches

- What is a fusée and chain mechanism in watchmaking?

It’s a centuries-old transmission system using a conical fusée and miniature chain to equalize torque from the mainspring. It provides more consistent force to the movement as the mainspring unwinds. - How does the fusée and chain system improve timekeeping?

As the mainspring loses tension, the chain moves to a wider section of the fusée cone, increasing leverage and balancing torque. This helps maintain accuracy over the full power reserve. - Are fusée and chain watches still made today?

Yes, though rare, some high-end watchmakers like A. Lange & Söhne, Breguet, and Zenith continue to produce modern wristwatches with this mechanism. - What challenges does the fusée and chain present in modern watches?

The system adds thickness to the movement and requires additional mechanisms for maintaining power during winding. It’s also expensive and complex to service. - Why would someone buy a fusée and chain watch?

While less practical than modern constant force mechanisms, collectors value the fusée and chain for its historical importance, mechanical complexity, and aesthetic appeal through display casebacks. - Which modern watches use the fusée and chain?

Notable examples include the A. Lange & Söhne Richard Lange “Pour le Mérite,” the Breguet La Tradition Fusée Tourbillon, and the Zenith Academy Georges Favre-Jacot. - Is the fusée and chain more effective than other constant force mechanisms?

While it does smooth out torque, other options like remontoirs, multiple barrels, and advanced spring materials are more compact and efficient in modern watchmaking.