Breguet Launches The 250th Anniversary Expérimentale 1, With Magnetic Escapement

How it works, why it works, and what this 10Hz tourbillon means for watchmaking.

This week, there was a piece of horological news so big that it eclipsed not only the news from this week, but the news from last month and maybe from the entire year. For the celebration of its 250th Anniversary, Breguet has been launching some fascinating and very thought provoking watches, including the ref. 7225, with magnetic pivots, running at 10Hz/72,000 vph. The latest release from Breguet, however, is something virtually unheard of in modern watchmaking: a watch with a magnetic escapement, also running at 10Hz/72,000 vph, and, like the 7225, rated to a maximum daily deviation in rate of just ±1 second per day. This makes it a watch in the top category for precision in Breguet watches: the Scientific category (the other two categories are Evening at -2/+6 seconds, which is already better than the COSC chronometer spec; and Civilian at ± 2 seconds per day.)

The Expérimentale 1 was announced as the first in a series of Expérimentale watches, which according to Breguet, will “incorporate the latest innovations from its Research and Development department.” The Expérimentale was also announced as the last of the 250th Anniversary releases, which came as a bit of a surprise to some of us patent-watchers out there, since Breguet had recently filed a patent for a Sympathique clock and watch (although hey, it’s only December 1, there’s still time for a “oh, and one more thing” moment).

Magnetism In Watchmaking, And Magnetic Escapements

The Expérimentale’s magnetic escapement is not the first, but it’s close. There is at least one other example of a magnetic escapement – the Clifford magnetic escapement, which was invented by Cecil F. Clifford, BSC, FBHI, in 1938, and for which he received a patent in 1956. Breguet, famously, has used magnets to suspend the pivots of balance staffs in two of its watches (so far), and TAG Heuer has used magnets instead of balance springs intermittently, starting in 2010 with the Carrera Pendulum (a concept watch that was never released commercially) and in a few others, including the MikropendulumS chronograph and tourbillon. Clifford’s magnetic escapement exists in a couple of known prototypes, made by Hamilton, but his design turned out to be a big, if temporary, success in clocks made by Horstmann Clifford Magnetics Ltd.

The idea of using magnetism as a restoring force (a balance spring substitute, in other words) is older than you might think – quite a lot older, as it turns out. In 1667, in his History Of The Royal Society Of London, Thomas Sprat wrote of “Several new kinds of Pendulum Watches for the Pocket, wherein the motion is regulated, by Springs or Weights, or Loadstones, or Flies moving very exactly regular.”

Although magnets can be used as suspension systems for pivots, or as substitutes for balance springs, and even for speed governors in chiming watches, actual magnetic escapements are, aside from the Clifford and now Breguet escapements, almost unknown (there is a Rolex patent for an escapement with magnetic banking pins which has some similarities with a chronometer detent escapement, but as far as I can tell these function as part of the mechanism for locking and unlocking the escape wheel). A magnetic escapement, it seems to me, is distinguished from other horological applications of magnets by the fact that magnetic fields are used to impulse the oscillator. This definition is actually fairly broad, in that it can include electromechanical watches like those made by Lip, Hamilton, Elgin, Citizen, and others, and it also includes the Accutron, and other tuning fork movements, as well as electromagnetically impulsed high precision pendulum clocks like the Shortt-Synchronome clocks.

However, the Breguet magnetic escapement seems to be genuinely unique. It requires no external power source, and the principles of its operation are somewhat similar to the Clifford magnetic escapement, but only in principle – the Breguet magnetic escapement is almost totally unlike the Clifford in just about every respect you can imagine.

Breguet’s Magnetic Escapement: Why, And How

A magnetic escapement – that is, one which delivers impulse via magnetic energy – could deliver something that horologists have been searching for since the beginning of mechanical watch and clockmaking, which is a true constant force escapement. Actual constant force escapements have been experimented with on several occasions, although they have never been widely adopted – Breguet was one watchmaker who produced them; Thomas Mudge’s “Blue” and “Green” sea clocks used constant force escapements, and more recently, Girard-Perregaux Neo Constant Escapement (which is based on a design originally patented by Rolex) is an example of a true constant force escapement as well (as opposed to a watch with a constant force mechanism, like the fusée and chain, or the remontoir). A magnetic escapement could deliver exactly the same energy for every impulse, and moreover, it could if designed properly, deliver impulse energy completely independently of the energy in the mainspring. There are of course technical hurdles – including the fact that magnetic field strength varies with temperature, and that magnets lose field strength over time – but in theory, a magnetic escapement could offer unvaryingly excellent performance.

Expérimentale 1 combines a magnetic escapement with a one minute tourbillon and a 10Hz/72,000 balance, and combining each of those elements with each other produced some unique engineering challenges.

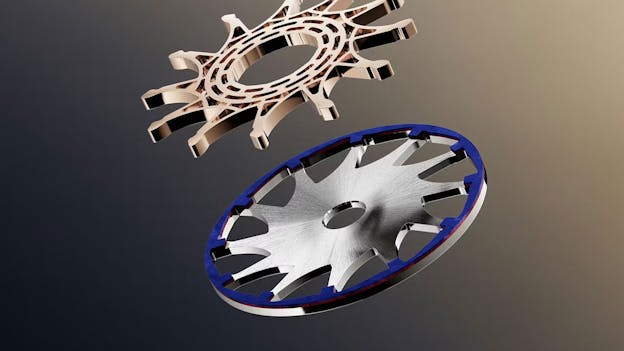

This is the tourbillon carriage, escapement, and balance for the Expérimentale. The platform is driven by the going train from its periphery (via the gear teeth on the edge of the platform). In a conventional tourbillon, the pinion of the escape wheel rotates around a fixed fourth wheel and turns as its pinion leaves work against the fixed fourth wheel teeth, and the balance and spring are on the center axis of the carriage. Here, you’ll notice that there is an intermediate driving wheel for the escape wheel, and it’s this driving wheel whose pinion rotates against the fixed wheel below the carriage. The reason for this is an interesting one – at 10Hz the escape wheel, which has 12 “teeth” (the scare quotes are there for a reason, which we’ll see in a minute) makes 100 rotations a minute, and the intermediate wheel is there to step down the fast rotation of the escape wheel so that the tourbillon rotates once per minute. This intermediate wheel shows up in one of Breguet’s magnetic escapement patents, which says, “The intermediate wheel set is a reducer wheel set of the rotational frequency of the escape wheel set and is herein arranged such that the tourbillon carriage performs one revolution on itself per minute.” The patent also says (it says a lot) that one of the inherent advantages of the escapement is that it lends itself to high frequencies. You can see the going train gears for driving the tourbillon carriage in the exploded diagram from Breguet; they’re grouped at the upper left, just below the triangular blue bridge which holds their upper pivots.

You’ll also notice if you look closely, that the Expérimentale has two mainspring barrels, but there are two mainsprings per barrel – the mainsprings run in series, which contributes to the Expérimentale’s 72 hour power reserve.

The actual magnetic escapement is under a bridge shared with the reducer wheel, and it is a head-scratcher at first. It looks like some sort of lever escapement on steroids but its specific operation is very, very different.

The Escapement As Transducer

Understanding how the escapement works, is I think easier if you think of it as a transducer. A transducer is any device that changes energy from one form to another. The Expérimentale escapement can be thought of as a transducer which converts mechanical energy from the mainspring and going train, to magnetic energy at the escape wheel/lever interface, and then back to mechanical energy again, as the lever impulses the balance.

The escape wheel not just a single wheel; instead, it’s made of three superimposed wheels . The upper and lower wheels have ring shaped permanent magnets fitted to their inner surfaces. Between them is a stop wheel, which interacts alternately with the left or right pallet of the lever. There are also banking pins (not shown) on either side of the shaft of the lever itself.

In this exploded view, you can see the two magnetic rings on the inner surfaces of the upper and lower escape wheels, as well as two tiny magnets fitted inside the left and right arms of the lever. The north poles of these magnets are shown in red, and the south poles are blue (remember that magnets are dipoles. There is always a north and south pole; if you cut a bar magnet in half, you get two new smaller magnets, each with its own north and south pole). The magnetic rings likewise have north and south poles, also shown in red (north) and blue (south). You’ll notice that the magnets in the lever – we can call them magnetic pallets, after the pallet jewels in conventional lever escapements – and the magnetic rings, are arranged so that if one of the pallet magnets is in between the two magnetic rings, a repulsive force will be generated, causing the lever to rotate on its pivot (like magnetic poles repel each other). This repulsive magnetic force is what produces the mechanical deflection of the lever, which is transmitted to the balance as a mechanical impulse. Impulse is delivered in both directions, and, since the impulse jewel of the balance sits in the pallet fork when the watch is not running, the escapement is self starting – one of the essential prerequisites for a wristwatch escapement.

In order for the escapement to actually run, however, there needs to be a way for the going train to “load” the magnetic potential energy of the escapement. To do this, there must be a gradient in the magnetic field produced by the ring magnets, in which the most powerful repulsive force is applied on the impulse pallet, and the weakest, on the re-entering pallet, as it drops into the space between the magnetic rings. The gradient is produced by the geometry of the magnetic rings as seen in profile – the segment of the rings that produces the strongest repulsive (impulse) force is the thickest section, and the segment which allows the returning pallet to move into position between the rings is the thinnest:

For the whole thing to work, for each beat of the escapement there must be an initial state in which magnetic potential energy is highest on the impulse pallet, and lowest on the returning pallet. You can actually see the entire cycle repeated twice in Breguet’s introductory video, starting at about 33 seconds in, but it’s blink-and-you-miss-it:

Let’s break the sequence down. In the initial state, the impulse pallet is adjacent to, but not directly above the thickest (and therefore, most powerfully repulsive) part of the magnetic ring:

The bronze colored stop wheel presses against the pallet, under pressure from the intermediate wheel and the going train – logically this ought to press the upper side of the lever’s shaft against one of the banking pins, holding the escape wheel fixed in position.

At this point the balance enters the pallet fork, and begins to unlock the pallet.

As the impulse pallet begins to move away from the escape wheels, it passes over the more powerfully repulsive/thicker segment of the magnetic ring. The repulsive force is transmitted to the balance via the impulse jewel. Note that the escape wheel is not yet rotating; it is prevented from doing so by the magnetic repulsive force exerted against the pallet. This means that the impulse energy is totally independent of the torque in the intermediate/reducer wheel, and the going train.

Once impulse has been given, the pallet has moved far enough away from the magnetic ring, that the escape wheel set can rotate, under the energy from the going train.

As the magnetic ring rotates past the pallet, the segment of the ring with the weakest repulsive force passes under the pallet. The other pallet (not shown) is now in position over the most repulsive part of the magnetic ring, re-arming the system for the next oscillation and next impulse cycle. The pallet which has just given impulse, is now free to re-enter the space between the rings closest to the most repulsive segment, and re-arm for its next impulse cycle:

And the pallet is now reset to give impulse again. The transition between the last two pictures takes almost no time at all, it is exceedingly rapid and my guess is that one of the functions of the stop lever is to make sure that each of the pallets is positioned precisely, in order to delivery the maximum impulse associated with the most repulsive part of the magnetic ring.

The moment when mechanical energy is converted into magnetic energy, occurs when the escape wheel set, rotates under the influence of the reducer wheel and the going train. This release of mechanical energy is what re-arms the impulse pallet at the most repulsive segment of the magnetic rings, rotates into position. Without the mechanical energy rotating the escape wheel set, the system would reach magnetic field strength equilibrium between the two pallets, and the watch would stop.

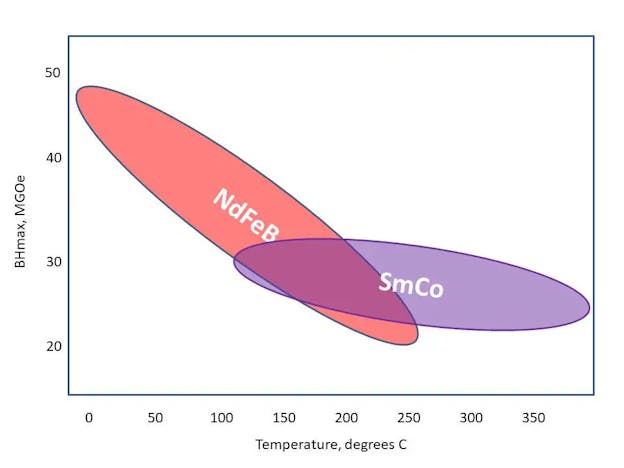

A person could be forgiven for wondering why it is that magnetic escapements were not more widely used – our horological ancestors were after all, enterprising and hypercompetitive people any one of whom would be absolutely delighted to patent a quantum leap in constant force escapements. I think part of the issue, as is so often the case in the history of watchmaking, is that there were simply technical barriers too difficult to overcome at the time. Magnets tend to lose power over time, and magnetic field strength is very susceptible to temperature variation, and these escapements require extremely small but very powerful permanent magnets – ideally, ones which will not show variations in field strength at typical ambient operating temperatures, and which can be relied on to take decades to weaken. The two primary types are samarium-cobalt and neodymium-iron-boron, which were developed in the 1960s and 1970s, and by then, nobody was going to try and make a magnetic escapement when quartz ruled the roost. Today, though, there is enough interest in mechanical horology, and enough of a fascination with innovation in the art, to make it worthwhile. The magnets in the Expérimentale 1 are samarium-cobalt, which is actually the older of the two main types, but it’s also, of the two, the one most resistant to field strength variations in temperature:

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets can be stronger, but samarium-cobalt’s much more temperature stable and if your Expérimentale is at an ambient temp of 100ºC, you may have other problems (image source).

Finally, I think this watch is very interesting as a design exercise. The Marine line has been in the past, somewhat hit or miss occasionally, and creating something really contemporary which also respects key Breguet design codes is very difficult to do. I think the design team at Breguet did an admirable job at updating the basic flavor of the Marine line into something that’s contemporary and luxurious in feel, and I would love to see what Breguet does in the next few years with these basic design codes; I can think of half a dozen Marines I’d love to see in this interpretation without breaking a sweat.

I have a couple of questions out to Breguet’s product team and will update the story as more info comes in but I think (hope) I have the basics right; in the words of Sherlock Holmes, “It’s only an hypothesis, Watson, but I venture to suggest that it fits the facts!” He also said, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data,” so, you know, you pays your money and you takes your chances. But I think the essentials more or less speak for themselves. One hell of a way to end the quarter millenium anniversary … now we just have to see whether or not somebody’s still got a Sympathique up their sleeve.

Note: since this story was published, Breguet has clarified some points on the action of the escapement. The pallets and stop wheel do make contact on every drop however, they then recoil very slightly from each other so there is no direct physical contact when the balance unlocks the lever and the impulse phase begins. A watchmaker from Breguet also clarified that there is “the magnetic equivalent of draw” – after a pallet has dropped but before the impulse phase begins, there is lateral repulsive pressure between the pallet and escape wheel stack. This prevents the escape wheel stack from rotating, but it also presses the shaft of the lever against one of the banking pins, preventing the lever from moving until it is physically unlocked by the balance. See this update for more details.

The Breguet Expérimentale 1, ref. E001BH/S9/5ZV: case, 18k Breguet Gold, 43.5mm x 13.30mm, lugs with blue ALD treated gold inlay; crown with blue ALD treated sandblasted gold inlay; sapphire crystals front and back, and 100M water resistance. Regulator type display; chapter ring, seconds ring and hands treated with blue emission Super-LumiNova. Movement, caliber 7250, 6.3mm x 33.8mm, Breguet certified “Scientific” category; two series coupled barrels with 72 hour power reserve; frequency, 10Hz/72,000 vph in 37 jewels. Constant force magnetic escapement with grade 2 titanium escape wheel and NiP12, nickel phosphorus LIGA etched pallet wheel; Breguet balance with flat silicon balance spring and non-magnetic balance staff. 75 piece limited edition, price at launch, CHF 320,000. See it at Breguet.com.

The 1916 Company is proud to be an authorized retailer for Montres Breguet.