Blancpain’s New Grand Double Sonnerie: Music For The Ear, Magic For The Mind

The Blancpain Grand Double Sonnerie sets a new and very high bar for chiming complications.

You could be forgiven for thinking that Blancpain has been going through a phase of general disinterest in innovating in the world of complicated watchmaking, although it’s worth remembering that when Blancpain showed its first watches of the modern era in 1990, one of them was the Blancpain 1735 – a minute repeater, perpetual calendar, rattrapante chronograph with moonphase and tourbillon; complicated watchmaking is at the foundation of Blancpain’s identity as a modern brand. Since then Blancpain has produced some quite interesting and sometimes completely unique complications, such as the Villeret Tourbillon Carrousel, which combines Blancpain’s flying tourbillon with a Bonniksen karrusel (another type of revolving platform for the escapement, balance, and balance spring; Blancpain is the only watchmaker to use a Bonniksen karrusel, much less combine it with a flying tourbillon.)

Today Blancpain has announced something really remarkable: a new complicated timepiece which breaks new ground on several fronts. The watch is the Grande Double Sonnerie, ref. 15GSQ 1513 55B / 15GSQ 3613 55B and the watch is even more complicated than its reference number: it is a Grande et Petite Sonnerie, with minute repeater, as well as a newly developed compact retrograde perpetual calendar, and Blancpain’s flying tourbillon, which was originally designed for Blancpain by AHCI member Vincent Calabrese, in 1989. As it turns out Blancpain, under CEO Marc Hayek (who is also responsible for the other Swatch Group prestige brands, including Jaquet Droz, Breguet, and Glashütte Original) had not lost interest in complications at all – it was just working on a project that would end up taking eight years to bring to fruition.

The watch measures 47mm x 14.50mm, but every inch of interior real estate (and exteriror real estate) has a purpose.

The Dial, In Depth

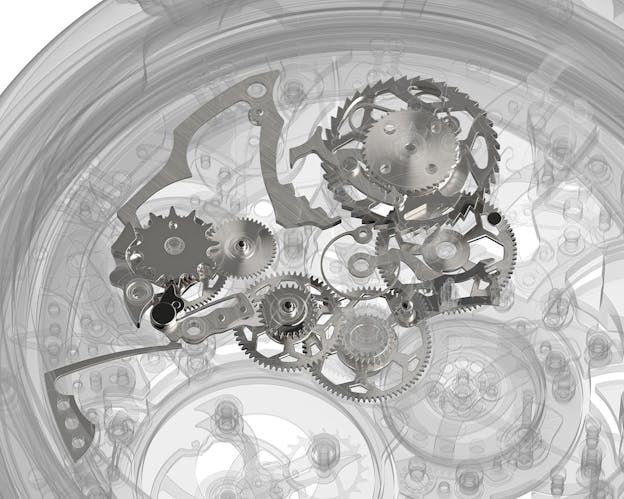

Seen from the front, you can see the four hammers for the striking system, the flying tourbillon, and the indications for the perpetual calendar.

On the left side of the case, there are two pushers that resemble those used for chronographs. One pusher is for selecting which of the two tunes the grande sonnerie will play; the other is for activating the minute repeater function. In the middle is a selector switch, allowing you to choose the strike mode. In grand strike mode, the watch will chime the full hours, quarters, and minutes at each quarter hour. The two tunes played each consist of four measures, and at each quarter, a progressively longer segement of the tune is played, with the full four measures playing at the top of the hour. In small strike (petite sonnerie) mode, only the quarters sound and the hour strike is omitted (you might choose to set the watch to petite sonnerie mode if you wanted to have a longer power reserve for the striking train). And in silent mode there are of course, no notes struck at all.

The date hand for the retrograde perpetual calendar pivots at the center of the dial, co-axial with the hour and minute hands, and the day of the week is in the upper of two subdials, with the month and leap year indications in the lower of two subdials.

Finally, there is an indicator showing which tune will be played for the quarters. The two tunes are the famous Westminster Chimes, or a special melody composed for Blancpain, by Eric Singer, who is the drummer for the rock band Kiss, but who is also a well known and very serious watch collector and enthusiast. If the Westminster Chimes are chosen, the letter W is displayed; if the Blancpain tune composed by Singer is selected, the letter B is displayed (as seen below).

The watch was designed so that all of the striking train components could be largely visible when the watch is worn on the wrist. Normally, the hammers and gongs for repeaters and grande et petite sonneries are on the back of the movement, with the racks and levers that control striking hidden under the dial. The governor, which controls the tempo of the chimes – that is, the speed at which the chimes are struck – is also usually on the back. However, it’s possible to construct a striking watch with an inverted movement architecture, although it’s relatively uncommon. That’s what Blancpain has chosen to do here, so that the action of the hammers on the gongs, and of the governor, would be visible.

Blancpain Caliber 15GSQ

The movement in the Grand Double Sonnerie, caliber 15GSQ, is a combination of existing and new innovations in both layout and basic engineering. Blancpain says, and I have no reason to doubt it, that it is the most complicated movement they have ever made, with 1,053 components total (including movement jewels). For this sort of watch, the movement really is the watch; other elements of the design matter, of course – at this level, everything does – but the movement is obviously the picture in the frame. Cal. 15GSQ is larger than the 30mm generally considered typical for wristwatch movements (this is based on the historical fact of that diameter being the maximum size allowed for wristwatch calibers in the observatory competitions) at 35.90mm x 8.50mm, but the details of its construction allow it to be very thin for its complexity; Grande et petite sonneries are a lot of things but thin is usually not one of them.

An Unusually Compact Perpetual Calendar

The architecture of the movement is also unusual in terms of the location of the perpetual calendar mechanism. Generally speaking, perpetual calendar complications are under the dial and are distributed across a single layer, which sits on top of the movement base.

The picture above shows the general layout followed by most perpetual calendars; the cam for months is up top, with notches for a full 48 month Leap Year cycle. The center of the complication is taken up by a single complicated, multi-armed lever which coordinates the switching of all the complications (this movement image is of a pocket watch grand complication made by A. Lange & Söhne in 1902. Following this approach (which, with some modifications, is that used by most perpetual calendars even today) would have made the Blancpain Grand Double Sonnerie considerably thicker, and would also have blocked the view of the striking mechanism and considerably reduced the transparency of the watch. Blancpain therefore decided to design a new perpetual calendar mechanism which could fit mostly on the right hand side of the watch, freeing the left and lower areas of the dial for displaying the tourbillon and the hammers and governor.

This is the perpetual calendar mechanism as see from the back of the watch – you can see the cam for the months to the upper left, directly under the subdial for the month and leap year indications, with the stacked gears to the upper right located under the subdial for the day of the week.

The action of the retrograde date hand at the end of the month is controlled by the long, thin spring on the far left, which presses on the foot of a rack attached to an intermediate wheel which drives the flyback gear on which the retrograde date hand is mounted. The mechanism is ingeniously compact and allows ample room for viewing the chiming works both back and front, while still leaving space for the flying tourbillon.

The Flying Tourbillon

The Blancpain flying tourbillon designed by Calabrese, differs from most other tourbillons in the arrangement of the components inside the cage. Normally, the balance in a tourbillon is co-axial with the axis of the cage, but in Calabrese’s design, the balance is shifted off center.

In a conventional tourbillon, therefore, the escape wheel is located under the balance, while in the Blancpain tourbillon, it lies almost on the same plane as the balance. The tourbillon cage is driven from below in the usual way and the cage rotates on its center axis around a fixed fourth wheel, whose teeth gear to the pinion leaves of the escape wheel. The Grand Double Sonnerie uses a flat silicon balance spring, and a freesprung, adjustable mass balance.

Blancpain had an advantage in their tourbillon in terms of keeping the thickness of the Grande Double Sonnerie manageable, since both as a flying tourbillon, and in terms of the specifics of its engineering, it uses less height than a standard tourbillon.

Two Tunes, Four Notes: The Grande et Petite Sonnerie

The Double Grande Sonnerie allows the user to choose one of two tunes for the striking of the time, and as we have mentioned one melody is the Chimes of Westminster, while the other is the Blancpain melody composed by Eric Singer. Both melodies are the same length, and take the same amount of time to strike.

One of the restrictions Singer was faced with when composing the “Melodie Blancpain” was that since it plays on the same gongs as the Westminster Chimes, Singer was restricted to using the same notes – E, G, F, and B, and could only vary their order.

We should preface any discussion of the Grande Double Sonnerie by noting that a grande et petite sonnerie of any kind is a rarity in a wristwatch. The complexity of the mechanism confined it to large chiming pocket watches, so big that they are sometimes called clockwatches, and reducing the complication to wristwatch dimensions didn’t happen until Philippe Dufour produced his grande sonnerie, shown at Baselworld in 1992. Since then they have been made in extremely small numbers and by relatively few brands and individual independents; among the few are Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and F.P. Journe.

Grande et petite sonneries usually also incorporate a minute repeater, but differ from repeaters in certain key respects. First, sonneries chime the time “en passant” or in passing; that is to say, when the sonnerie is activated the time will be struck at the hours and quarters without the need for any action on the part of the owner. Repeaters, in contrast, chime the time on demand, whenever a slide in the case is pushed home. The repeater is powered by a smaller, separate mainspring which is wound up when the slide is pushed.

Both repeaters and grande sonneries use a system of cams, racks, and levers to chime the time. All chiming complications contain cams, or snails, for the hours, quarter hours, and minutes. The minute snail has four arms – it looks a bit like a starfish – each of which has fourteen steps, for each of the fourteen minutes which can chime after a quarter hour is reached. When the repeater is activated, a rack with fourteen teeth on it, pivots and its tip falls onto the minute rack. How far the rack falls depends on how far the minute snail has rotated; if it is fourteen minutes past the last quarter, the rack will fall onto the lowest of the fourteen steps. The rack is then rotated back to its starting point by a gear driven by the repeater mainspring. As it moves back to its starting point, the teeth on the rack flick small trips (or “lifts,” to translate the French term “levée”) which in turn, flip the shafts of the hammers so that they strike the gongs. If the rack has fallen onto the fourteenth step, fourteen of its teeth will pass the trips and the minute gong will sound fourteen times. This is the basic principle behind the hour and quarter hour strikes as well, except that the hour and quarter snails have twelve and four steps respectively.

A grande et petite sonnerie is driven by a very large second mainspring barrel which is wound up at the crown of the watch; this barrel can be even larger than the primary mainspring barrel as it has to power the strike train four times per hour. Minute repeating, in a grande et petite sonnerie, repetition minutes, is also driven off the same barrel. The size of the mainspring barrel for the chiming works determines how long chiming in passing can take place; for the Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie, the power reserve in full strike mode is 12 hours.

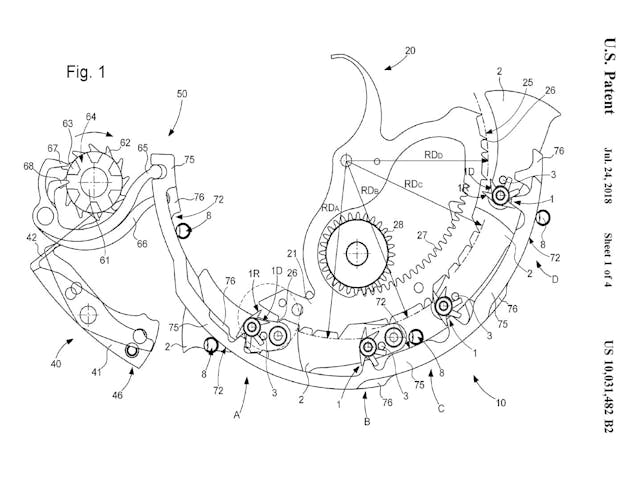

The Westminster Chimes and Blancpain Melody both strike on the quarter hours, and so the tunes are struck by the quarter rack. Since the quarter rack must strike as many as sixteen notes (for a full quarter strike at the top of the hour) the rack must have sixteen teeth, which are arranged so as to flick the trips, or lifts, of one of the four hammers as the rack passes the teeth. And, since the Grande Double Sonnerie must play either of two distinct melodies, Blancpain designed the quarter rack to have two different levels, superimposed on each other – one for the Westminster Chimes, and one for the Blancpain melody.

The striking mechanism is shown here with the minute and quarter snails (the hour snail is translucent, but it’s directly below the quarter and and minute snails). The quarter rack, with its two layer construction, is shown, along with the upper and lower sets of teeth for flicking the trips (or lifting the lifts, you could say). The four trips, one for each hammer, have upper and lower teeth as well. When the quarter rack pivots and falls onto the quarter snail, the teeth on the rack flick the trips but without causing them to lift and drop the hammers (in the picture, when the rack falls it rotates counterclockwise and the trips are lifted clockwise). When the gear inside the quarter rack rotates the quarter rack back into its resting position, the teeth on the quarter rack lift the trips, making them rotate counterclockwise (from this perspective) and lift and drop the hammers, causing them to strike the gongs.

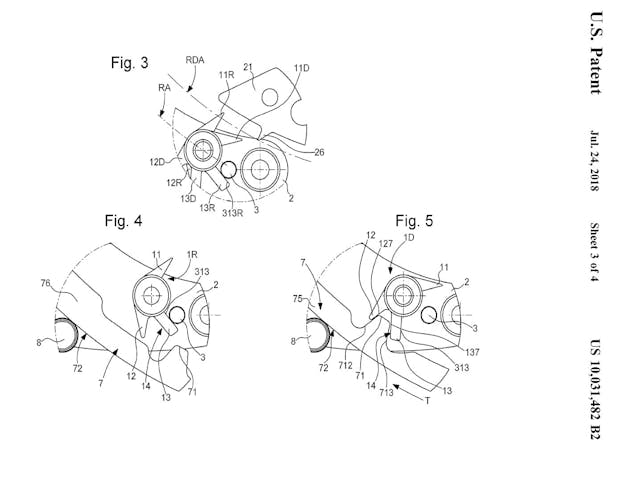

This illustration shows the arrangement of the quarter rack and trips more clearly, and also shows the quarter snail on the right. The switching mechanism for controlling which melody chimes, consists of the column wheel to the right, which controls the position of the two selector slides. When a melody is chosen, one of the slides rotates along its arc, lifting the teeth of one set of trips away from the quarter rack; the quarter rack will now pass those teeth without interacting with them. At the same time, the other slide rotates the other set of trips so that their teeth now lie in the path of the quarter rack teeth – the upper set for one melody, the lower set for the other.

In the above illustration, the upper control side has rotated clockwise and lifted the trips for the upper set of quarter rack teeth, out of position. At the same time, the lower slide has released the lower set of trips so that they now lie in the path of the lower set of teeth on the quarter rack.

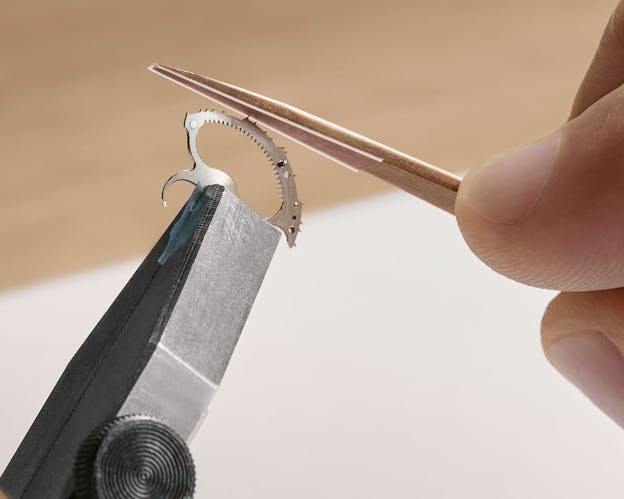

If you’re wondering what prevents the trips being lifted out of the path of the quarter rack teeth from accidentally dropping into their active position, they are held in place by blade springs which press on the tabs on the opposite side of the teeth of each trip. These can be seen in a demonstration model shown to visitors at the exhibition area in Le Brassus, set up to introduce the watch to visitors.

The model shows the jumper springs for each of the trips – you can see that there are two for each trip; one for each level – as well as the control slides, double layer quarter rack, column wheel, the column wheel switching levers and their associated jumper springs, and the minute and quarter snails. In the back you can see the arms of two of the four gongs.

Naturally the mechanism is protected by a patent – there are a total of 21 patents associated with the watch. The above drawings show another perspective on the quarter strike system for selecting the melody, as well as (lower image) a closer view of the trips, or lifts.

The above image shows the entire striking and selecting mechanism in situ, installed in the watch.

It goes without saying that these components are both quite small, and have to be machined to a very high level of precision for the mechanism to work at all. Typically, such high precision machining is done with EDM/spark erosion machines, but there is considerable fine tuning which still has to be done to ensure the timing and strength of the individual strikes is correct.

Making Music: Adjusting Tempo, Timbre, And Tone

The gongs themselves are gold, and machined using spark erosion, but even after they are delivered, they have to be tuned so that they produce the exact correct notes as well as pleasing secondary harmonics. Tuning of the gongs is checked by means of a laser measuring device, which isolates the primary frequency as well as the associated harmonics. The actual tone is adjusted using the traditional method of filing down the tip of the gong to correct the frequency, which is done in increments of as little as one micron.

As the gongs are both visual and technical components, their surfaces are also polished by hand.

The tips of the teeth of the quarter rack are also filed by hand to adjust timing – the tolerance for tempo is a precision of 5/100 of a second.

Adjustments once again can be made in increments as small as one micron (for reference, the average diameter of a human red blood cell is around five microns).

The overall pace, or tempo, of the chimes is controlled in chiming watches by a governor. Governors historically have been one of two types: anchor governors, which produce a fairly loud and easily audible buzzing noise, and centrifugal governors, which are much quieter but which still produce a faintly audible whirring sound. The Grande Double Sonnerie uses a magnetic governor, which was originally developed for Breguet and used for the first time in the Classique La Musicale.

The governor consists of a central rotor, with two wing shaped plates held close to the axis of the rotor by two C-shaped springs. The plates are made of silver, and when the watch begins to chime, the rotor begins to spin, causing the wings to extend and interact with small but powerful permanent magnets on rings just above and below the rotor itself. This induces what is called an eddy current in the rotor plates, which in turn produces a magnetic field that opposes the fields of the permanent magnets (Grand Seiko’s Spring Drive works in a similar fashion, although in that case, the magnets are electromagnets and the induced braking force is controlled by the quartz timing package). The system is almost totally silent. In order to prevent any magnetic interference with other components in the watch, the governor sits inside an antimagnetic housing, although the most potentially vulnerable component – the balance spring – is made of amagnetic silicon.

The governor is visible from the front of the watch, along with the other most dynamic components – the flying tourbillon, and the four hammers.

In order to ensure that the sound of the gongs can propogate through the case and crystal, without losing any of the lower harmonic tones (the loss of which can produce an unpleasantly bright sound) Blancpain has developed an inner membrane with a very complex cross section, which acts to conduct sound waves from the interior to the exterior of the watch without any loss of sound volume, quality, or clarity.

Hand Finishing: Beauty Made Visible

There has been a sort of reassessment of evaluating fine finishing in recent months among enthusiasts, propelled by the growing realization that it’s possible for CNC and other automated machine tools to produce consumer ready finished surfaces with little or no human intervention – and, moreover, that the idea that sharp internal corners, at least, cannot be machine made, turns out to be largely untrue. The consensus thus far is that if a brand is really hand finishing a movement, they’ll show you and Blancpain has showcased considerable handwork as the final stage in the creation of the Grande Double Sonnerie, prior to final assembly.

This is the upper bridge for the perpetual calendar works, and it contains a significant number of the total of 135 inward angles found in the Grande Double Sonnerie. The bridge, like the rest of the movement, is made of gold and is initially machined by CNC, before being hand finished. Hand finishing in this case involves finalizing all the interior angles by hand, finishing all the anglage by hand, straight graining the upper surface of the bridge with increasingly fine abrasive paper, and applying perlage to the underside of the bridge.

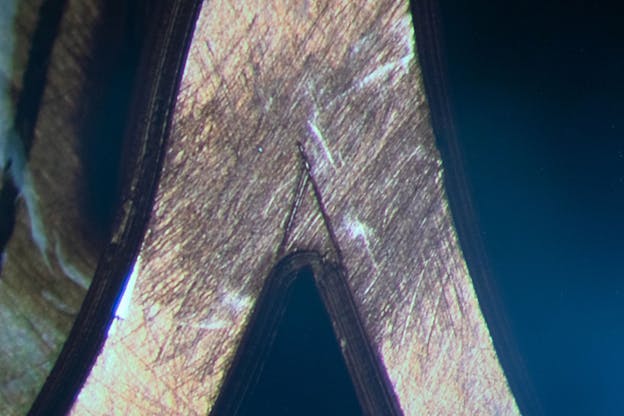

The bridge comes from the machine shop looking nothing like the final result, which gives you an idea just how much work is involved in bringing it to the proper level of finish. Here’s an example, shot from a monitor attached to a microscope being used by an artisan hand-finishing the inner angles, of what one of the inner angles looks like before it’s worked on.

As you can see, tool marks are visible on every surface, every one of which is hand finished after machine fabrication. If you look closely, you can see the marks of the (very small diameter) end mill of the CNC machine, as well as the radiused inner angle, which the finisher will sharpen with a graver. While the outer and inner bevels have been roughly established by CNC, they will all need to be polished – in this case, by hand, using the gentian wood tools and fine abrasive pastes that have been long been traditional in watchmaking.

While roughing out of components is done by automated milling machines, this is the case in virtually any high end watch you can think of, and there are a considerable number of techniques applied to the cal. 15GSQ by hand. These include the Geneva stripes, very fine perlage, black polishing of steel components (including the gongs) and polishing of all flanks, angles, and inner and outer corners, as well as straight graining or polishing of the upper surfaces of plates and bridges. You’re left with a strong impression of the considerable time and skill necessary to produce a perfectly finished component (and of the responsibility watchmakers assembling the watch must feel to not ruin someone else’s many hours of work).

A Machine Designed For Living

The Grande Double Sonnerie has been designed to be worn, if the owner wants to, on a daily basis, and several features have been incorporated to fulfill that goal. One of them is the presence of numerous safety features designed to prevent accidental damage to the movement. Setting the time, for instance, is blocked when the chimes are operating, and conversely, when the watch is being set, the chiming functions are disabled. In order to prevent incomplete striking, the striking mainspring is disengaged when the power reserve falls too low, and switching the melody selection is also blocked when the watch is striking.

The perpetual calendar can be set with Blancpain’s convenient system of correctors, located under the lugs, and which require no separate setting stylus.

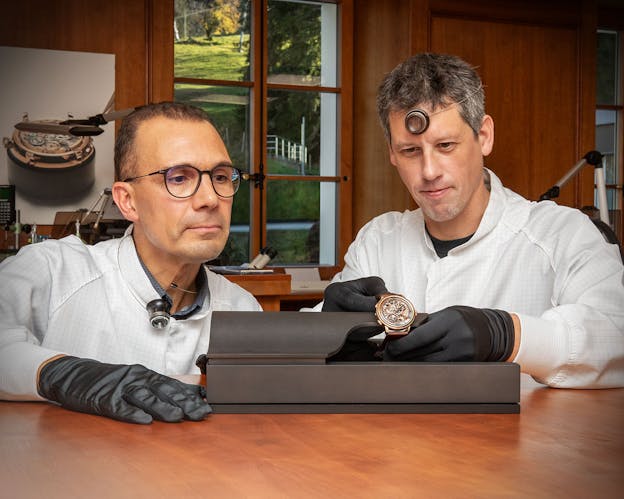

Two watchmakers, Romain and Yoann, are responsible for assembling each watch and the entire process can take nearly a year. In a gesture I hope we see more of in fine watchmaking, each watchmaker “signs” his work – there is a tiny plate attached to the movement with the engraved signature of each watchmaker.

The visit to Le Brassus to see this watch, and to see what actually goes into making it, was an intellectual and aesthetic experience the power of which is hard to convey, and it is hard to decide what’s more impressive – the engineering and mechanical ingenuity which went into the watch, or the labor that went into making it an object as beautiful as it is clever. Having both expressed to a high degree in a single object, is of course the whole point of fine watchmaking, or it should be the point. Blancpain and Mark A. Hayek’s commitment to transparency and clarity in showing every major characteristic of the watch made for an incredible presentation and one which I hope as many people as possible can experience to some degree in years to come. The watch is not a limited edition per se, but only two can be made per year (with longer production times if customization is desired – Marc Hayek pointed out that modifying the melodies would be difficult, as any custom melody composed would have to follow the same restrictions that Eric Singer had to follow: four notes, four measures, four notes per measure). It’s bravura watchmaking, but at its best, and it’s a reminder that despite the fact that watchmaking is largely an incremental affair these days, it is still possible, with determination and imagination, to open up vistas to undiscovered countries.

The Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie: Case, red or white gold, sapphire crystals front and back; water resistance 1 bar/10 meters; 47.00mm x 14.50mm. Leaf hands in black oxidized gold. Movement, Blancpain caliber 15SQG, grande et petite sonnerie with minute repeater chiming the quarters on the user’s choice of two melodies; perpetual calendar with retrograde date; flying tourbillon; running at 4Hz in 67 jewels. Not a limited edition but production limited to two watches per year. Price starts at CHF 1.7 million. For more information, visit Blancpain.com.