The MB&F HM11 “Architect” Remembers Days Of Future Past

The HM11 is an homage to a world of tomorrow that never was.

1957 was, like most years, a year when quite a lot happened. More specifically, though, it was a year when the future seemed bright, albeit some of the illumination might be coming from mushroom clouds. It was the International Geophysical Year; it was the year that Nautilus, the first nuclear submarine, matched the distance traveled by the fictional submarine after which it had been named. It was the year of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite; it was the year Hugh Everett III published his paper on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, setting us up for both the notion of the multiverse, and a string of increasingly incoherent Marvel movie sequels; it was the year the laser was invented; it was the year the Civil Rights Act was passed. And it was the year that Disney, in the spirit of the times, opened a new attraction at Tomorrowland in Disneyland – the amazing, all-plastic Monsanto House Of The Future.

The Monsanto house was a collaboration between Monsanto (at the time a company focused mainly on plastics production rather than pesticides) Disney, and MIT, and was meant to showcase the potential of plastic as a material of the future capable of performing any miracle you might want to ask of it. The house had a four-lobed design, with rooms consisting of plastic shells cantilevered off a concrete base containing utilities like the heating and air conditioning systems. It featured cutting edge modern conveniences like a microwave oven in the central kitchen, because what modern family wants to cook with fire like some knuckle-dragging Homo heidelbergensis, when you can zap food (flash frozen!) in the radar range?

The Monsanto House turned out to be something of a one-off, and its organic forms (as well as all-plastic construction) have aged poorly as it turns out. The house itself didn’t get much of a chance to age at all. It was demolished in 1967, although it went down fighting; the structure was so tough that the half inch steel bolts holding the plastic shell onto its concrete base snapped before the plastic broke.

The image of the Monsanto House, however, has become one of the visual icons of the idyllic visions of the future of the 1950s and 1960s – the architectural version of The Jetsons, you might say. And it’s become an inspiration in a way that I bet would have surprised the earnest eggheads and starry eyed futurists who designed it, as one of the inspirations for the latest Horological Machine from MB&F – the HM11 Architect.

The connection between the Monsanto House (as well as other similar organic architecture homes of the era) is immediately obvious, although the watch also has – unsurprisingly from MB&F – a bit of an otherworldly, UFO-like look as well (the promotional video MB&F produced shows the watch as a house, sitting in the middle of an erg, or dune sea, which feels like either an homage to Dubai Watch Week, or to the Dune books, or, what’s most likely, to both). The Architect consists of a central flying tourbillon – this has been a signature element in many Machines, starting all the way back with HM1 in 2007 – with four wings extending outward from it, separated by framing structures that hold the various mechanisms in place. The entire mechanism sits on four anti-shock spring pillars, visible below at the diagonal quarters, in addition to the conventional antishock springs for the balance pivots.

There are three displays at three of the quadrants, and the fourth is occupied by the extremely large crown, which is used only for setting the time. Winding the watch is done by rotating the entire upper structure on its base, reflecting the living space above and utilities below structure of the Monsanto House. The crown, says MB&F, presented a problem in terms of gasketing thanks to its size; a gasket large enough for the interior diameter of the crown would have been large enough to generate so much friction that you wouldn’t be able to turn it. The solution was to use two sets of gaskets, with the larger of the two thin enough to keep dust out, and the much smaller gasket around the stem providing actual water resistance (20 meters; the crown has a total of eight gaskets associated with it).

Since the entire upper case rotates, you can turn whichever display you like into the uppermost position.

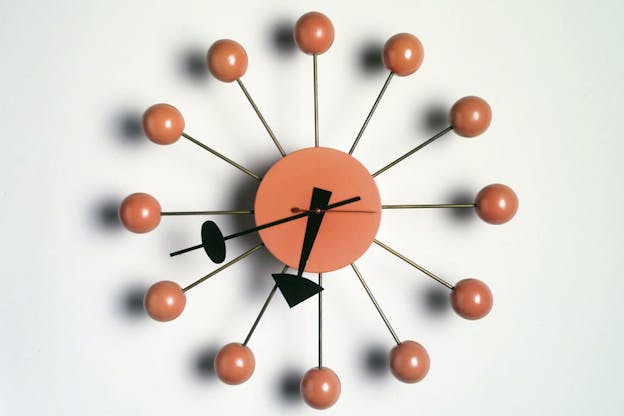

The first “room” contains the display for the time. The design is more or less conventional, with ball-shaped markers for the hours. The use of spheres as hour markers is a shout out to the famous Vitro ball-clocks, designed by George Nelson during his career as lead designer at Herman Miller.

The second “room” houses the power reserve indication, which is 96 hours.

Again, the overall design’s an homage to the Vitra ball clocks. The third “room” houses a complication which is fairly unusual for a modern wristwatch: a thermometer.

You can have the thermometer with either a Fahrenheit or Celcius scale. The reason wristwatches don’t tend to have thermometers is simply because if you’ve got one on your wrist, it will be affected by body temperature and you won’t get an exact reading. The design of the HM11 Architect elevates the thermometer above your skin, so presumably the precision of the thermometer will be less affected than if the case were directly against your wrist (although I’d imagine that body temperature would still affect it to some degree).

Thermometers as complications can be found in pocket watches more often than wristwatches; Breguet was fond of them and used them in many of his timepieces, including the lost-and-found Marie Antoinette. The basic principle behind his thermometers was the differing coefficient of expansion of different metals; you make a bimetallic strip, coil it into a spiral, and it will expand and contract as temperature changes. This is the same principle that was used in watches for compensating balances, before the widespread use of Nivarox-type balance springs. The usual metals for the coiled spiral are brass or copper, and steel (that’s what you’d use for a compensating balance as well) although MB&F says it’s using other alloys (not otherwise specified). Breguet used a complex three layer sandwich of platinum, gold, and silver for his most sensitive thermometers.

Finally, there’s the fourth “room” which consists of the large, transparent crown and double battle axe inset (the double battle axe motif has also been one MB&F has used since the first Horological Machine). MB&F, carrying on with the modernist home inspiration, describes the crown as analogous to the entryway of a house (although this is a bit of a departure from the Monsanto House, which you entered via a stairway flanking one of the pods).

The watch is available at launch in a Blue Edition (titanium case, PVD blue movement plate) or a Rose Gold Edition (titanium case, PVD rose gold movement plate). At 42mm x 23mm it is no bigger than some modern diver’s watches. Each version is a limited edition of 25 pieces, and the price at launch is CHF 198,000/USD 230,000.

With any MB&F Horological Machine, a lot of the success of the design is really based on how willing you are to first, buy into the whole idea of a watch not as an expression of utility or tradition, but as a jumping off point for combining the inherent fascination of a mechanism with an intersection with some non-horological source of design inspiration. The second thing that has to happen, is that you have to find any particular intersection an interesting one. Finally, you have to be wowed by the object as a whole, as a unified design, on an emotional level and it’s here I think that MB&F has succeeded extremely well – I have never seen a Horological Machine in person that didn’t make me exclaim, “Wow … that’s cool.”

The idea of a modern tourbillon wristwatch directly inspired by a piece of retro-futuristic architecture (rather than, say, a mid-century high performance sports car, a starship, or motifs from Japanese manga) seems like such a natural one for MB&F that the only thing that really surprises me is that it didn’t happen sooner. The watch also appeals to the childlike pleasure watch enthusiasts take in manipulating a timepiece, and in winding a hand-wound watch; basically the winding crown is the entire case and while this isn’t a new idea (the Ulysse Nardin Freak springs immediately to mind) the physical characteristics of the case would I think, make the HM11 especially enjoyable to wind.

In a sense, making a watch inspired by a house rather than by a some other more mobile design object, speaks a little bit to where Max Bûsser and MB&F find themselves in 2023. A house is intended, the untimely fate of the Monsanto House notwithstanding, to be a durable and enduring part of the horological landscape and Max and MB&F are well past the early enfant terrible stage and well into becoming respected institutions in the world of watchmaking.

The only reservation I have about the Architect – really, an observation more than a reservation – is that it is the most roundly symmetrical Horological Machine so far and it feels as if it’s crossing a bit into Legacy Machine territory, where the classical repose of a round case is the starting point for design. This is all by way of saying that this feels to me like the least transgressive Horological Machine MB&F has ever produced. That’s not a bad thing and some degree of crossover between the design languages of the Legacy Machines and the Horological Machines was probably inevitable.

All of Max’s work, or most of it, at MB&F and before that, as the guy behind the Harry Winston Opus models, has always been about finding an equilibrium between classical watchmaking and an unfettered imagination. MB&F is not the result of wanting to be transgressive per se in any case; the vibe is not Épater la bourgeoisie, so much as it is, “The question isn’t ‘why’ it’s ‘why not?’ That the Architect feels like such a calmly self-assured piece of design (to me, anyhow) is a feature, not a bug, and it makes me wonder, with all the formal experimentation it has under its belt, where MB&F will go from here.

The MB&F Horological Machine 11 “Architect:” case, grade 5 titanium; display markers consisting of conical stainless steel rods with beads in polished titanium and aluminum; 42mm x 23mm with 20M water resistance. Sapphire crystals front and back and on each of the faces and crown. Case consists of a total of 92 components. Movement, “horological engine” with display of the time, power reserve, and temperature via a thermometer with bimetallic coiled strip; central flying tourbillon running at 18,000 vph in 29 jewels. Limited edition; Blue or Rose Gold versions, 25 each worldwide. Price at launch, CHF 198,000/USD 230,000. For more information, visit MB&F.