A Twist On The Tourbillon: The Ulysse Nardin Freak ‘Freak Out’

In 2001, the Freak changed how we think of tourbillons forever.

The tourbillon is by and large, essentially the same from one watch to the next and has been so since Breguet was granted his patent in 1801. You know one when you see one: the balance, lever or other escapement, and escape wheel are all mounted on a rotating cage or carriage and the whole kit and kaboodle generally rotates once a minute. Different rotation speeds are possible; Omega’s wristwatch caliber 30 I, made for the observatory timing competitions, had a rotation of seven and a half minutes; Breguet made four minute tourbillons. Tourbillons usually have an upper bridge for the upper pivot of the cage, but in 1920 Alfred Helwig, at the Glashütte School Of Watchmaking, developed a tourbillon with no upper bridge, which is called a flying tourbillon.

The tourbillon is sometimes called a “tourbillon escapement” which is incorrect, as a tourbillon can be constructed with different escapements. Most tourbillons use some variation on the lever but you can make a tourbillon with a chronometer detent escapement as well.

A tourbillon is characterized by one essential feature, which is a non-rotating gear on whose axis the cage rotates. The lower pivot of the tourbillon cage is usually driven by the third wheel of the gear train – although again, different arrangements are possible – and as the cage turns, carrying the balance, escapement and escape wheel, the teeth on the pinion of the escape wheel turn against the teeth of the fixed wheel, which drives the lever and the balance.

In 2001 Ulysse Nardin launched a watch which forced the world of watchmaking to completely re-examine the existing definitions of the tourbillon. This watch was the Ulysse Nardin Freak. For this installment of A Watch A Week, we’re going to look at what you might call a classic example of the watch – the Freak Out, which was launched in 2018 and which has all the features that made the Freak such a groundbreaking watch in 2001.

The Freak was the first watch to use silicon components; it had a new type of escapement; and it was an entirely new type of tourbillon – or was it?

The Freak certainly doesn’t look like a tourbillon. The large case contains a mainspring that takes up the entire inner case diameter, and to wind the enormous mainspring, you turn the entire caseback, which is knurled to give you a better grip.

That mainspring is responsible for driving the entire movement to rotate once per hour – the entire gear train is contained in a linear bridge, with the first gear turning against a set of fixed, inward facing teeth on the inner bezel.

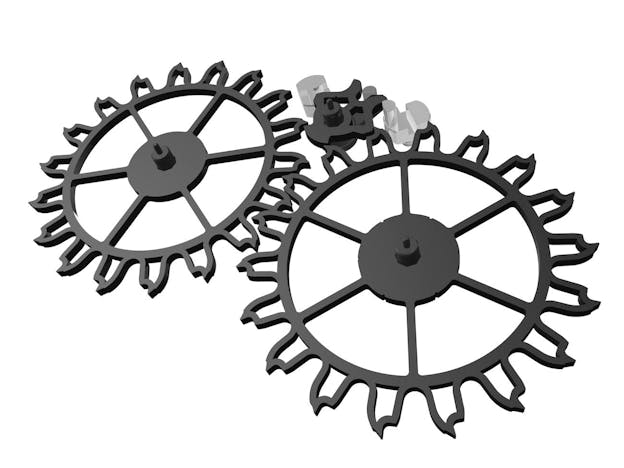

At the other end of the gear train, there’s a double wheel escapement – the Dual Ulysse escapement. This escapement is based on Breguet’s so called “natural” escapement, which had two escape wheels as well, both of which drove the balance directly. The Dual Ulysse escapement’s double escape wheels drive a small lever, taking turns impulsing it as it in turn impulses the balance.

The system requires no lubrication on the impulse surfaces and the impulse force is exactly symmetrical. The first version of this escapement, the Dual Direct, drove the escape wheel directly (like the Breguet natural escapement) but there was a basic design problem – each of the escape wheels had only five teeth on their entire circumference to impulse the balance, which meant each wheel was turning 72 degrees at every balance impulse. This was inherently inefficient and so, the Dual Direct escapement was updated to the Dual Ulysse.

The layout is wildly different from a conventional tourbillon but at the same time it is simple and ingenious. The first version of the Freak was designed by Carole Forestier, who won the Prix Abraham-Louis Breguet for the design in 1997 (the prize was awarded by the Breguet Foundation, in celebration of its 250th anniversary). The design was remarkable for a number of reasons, from a technical standpoint, the idea of basically putting the entire movement in a one hour tourbillon cage was highly imaginative and the same conceptual thread can be seen in Carole Forstier’s later work as Cartier’s head of movement design.

So is the Ulysse Nardin 2053-132/03.1 a tourbillon? I’m inclined to say yes, although I’m not sure how much the definition actually matters. However, if the most defining and basic characteristic of a tourbillon is the rotation of a platform carrying the balance and escapement around a fixed wheel, then it absolutely is a tourbillon.

As an experience, there was nothing like the Freak in 2001 and there’s still nothing like it today. It is in a way both a very traditional and very transgressive design – the traditional side of its appeal is in the way it takes the fascination of mechanics and really puts it front and center. A conventional watch, of course, does no such thing; even with a modern display back a conventional watch hides most of the action, most of the time. The dial is just for displaying information. With the Freak, and the Freak Out, the experience of the watch is synonymous with the experience of the mechanism – it’s as if after four centuries of watchmaking the movement has finally broken through to the surface. The iridescence of the silicon escape wheels and their spiderweb delicacy is a reminder as well that the watch is something born of a new era in watchmaking – the Freak could not exist without modern materials and methods.

Although independent watchmaking was already beginning to flourish in 2001, the Freak was the first of its kind: the first hyperwatch, in which design inspiration and cutting edge technology were exploited to create a new vision of watchmaking and a new sense of its unlimited potential. Since then some incredibly extravagant and bold designs have been created – and some of those designs have stood the test of time better than others. The Freak will always be what it was in 2001: an unprecedented vision of the shape of things to come.