It’s Tourbillon Day – Here’s Your Guide To Breguet’s Invention, And Why It’s Still Going Strong After 200 Years

It’s the 224th anniversary of Breguet’s patent.

Happy Tourbillon Day, to those who celebrate! If you’re so inclined, today’s the day to raise a glass to Abraham Louis Breguet’s most famous invention: the tourbillon, which he patented in 1801. At the time, the French Republican calendar was in effect – in keeping with the revolutionary government’s somewhat zealous idealism and its desire to sweep away as many trappings of the ancien régime as possible, they had adopted a calendar with twelve months, each consisting of three ten-day weeks. (Intercalary days – either five or six depending on the year – were added at the end of every year). The first month of summer in the calendar was Messidor (from the Latin “messis” or harvest) and Breguet’s patent was dated 7 Messidor, Year IX – June 26th, on the Gregorian calendar.

The Republican calendar only lasted a few years – it had a number of disadvantages, one of which was that it started on the Autumn Equinox and so New Year’s Day varied from one year to the next; but the tourbillon has carried on – in fact, not only has it carried on, it has become close to ubiquitous, at least in high end watchmaking.

There is hardly a major (or minor, for that matter) luxury watch brand which doesn’t have a tourbillon – AP, Patek, Vacheron, and Lange all have a plethora of models, and it is much harder to think of a luxury brand that doesn’t have a tourbillon offering than to name the ones that do. Even Grand Seiko has a tourbillon – the Kodo Constant Force Tourbillon; and although I don’t know that all that many of us remember it, Credor released the Fugaku Tourbillon in 2016.

What The Tourbillon Is (And What It Isn’t)

The tourbillon is unusual among complications in that strictly speaking, it is not a complication at all, but rather, a regulating device – the same is true of the fusée and chain, and the remontoir. Generally, complications are considered mechanisms that provide additional information or functionality – the simple, annual, and perpetual calendars are obvious examples, as are the chronograph and minute repeater. The tourbillon, on the other hand, provides no additional information or functionality, and in fact, if it were not for the fact that most tourbillons today are visible on the dial side of the watch, you would not know looking at a tourbillon wrist or pocket watch, that the mechanism was there at all.

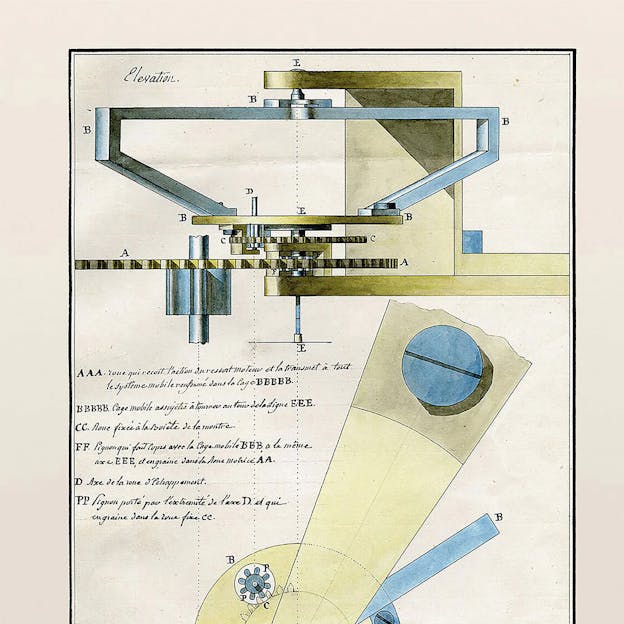

The tourbillon is also sometimes erroneously referred to as a tourbillon “escapement.” This is also incorrect – this is easy to see from the fact that a tourbillon can have any kind of escapement you like; there are tourbillons with lever escapements, tourbillons with detent escapements, tourbillons with the Breguet echappement naturel, and so on. The tourbillon cage contains the escape wheel, the escapement proper, the balance, and the balance spring. Normally, the movement third wheel turns the tourbillon cage, with the escape wheel pinion geared to the teeth of a fixed fourth wheel underneath the cage.

The purpose of the tourbillon has been described very succinctly by George Daniels, in Watchmaking: “The tourbillon, or rotating escapement carriage, was patented by A. L. Breguet in 1801. The purpose of the invention was to eliminate the errors of poise in the balance by revolving the escapement continuously to produce a uniform average rate.”

Breguet, in a letter to his son written in 1795, wrote,”I have succeeded in cancelling out the anomalies due to the different positions of the centre of gravity and the movement of the balance wheel by distributing the friction on the different parts of the balance and the holes in which the pivots move, to ensure that the lubrication of the frictional surfaces are always the same despite the coagulation of the oil; and thus to destroy many other causes of errors which influence to a greater or less extent the accuracy of the movement (of the balance) and which no method so far succeeded in eliminating, except with endless fumbling, with no certainty of success.”

“Endless fumbling with no certainty of success,” conveys a certain level of feeling; one gets the impression Breguet was writing from experience.

Essentially, the tourbillon is a partial solution to the problem of a watch running in different rates in different positions, due to the effects of gravity on the balance, spring, and escapement; the tourbillon takes all the vertical positions (traditionally a watch is timed in four vertical positions; crown up, down, crown left, and crown right) and creates a single average rate for all the vertical positions. Daniels wrote, “The close vertical rates obtainable with a tourbillon will last longer than similar rates from a conventional watch.”

What Constitutes A High Grade Tourbillon?

If the tourbillon is going to deliver, it should address certain points. As with any engineering solution, any given decision about the various features of a tourbillon represents certain tradeoffs, and it’s the intelligent balancing of often conflicting needs that gives tourbillon design its interest.

First of all, there is the escapement. The lever escapement is almost universally used in modern watchmaking and the same is true for tourbillon watches. However the lever escapement also relies on oil on the impulse faces of the lever jewels and escape wheel teeth. Daniels pointed out that the close rate expected from a tourbillon is best achieved with an escapement which doesn’t need oil, as the gradual deterioration of oil on impulse surfaces will eventually introduce additional errors in rate. Naturally this was an opportunity to plug the co-axial escapement, although he also pointed out that any oil free escapement (a chronometer detent, for instance) would do the job.

The chronometer detent escapement has its own issues, one of which is that it has a tendency to unlock accidentally if the watch is given a shock. The lever escapement requires oil but it has excellent “safety” as watchmakers put it – it is held firmly in place by the pressure of the going train except for the instant in which it gives impulse to the balance.

Then there is the speed of rotation. Tourbillons generally rotate once per minute. This is convenient as it lets you put a seconds hand on the top pivot of the cage. However, it is not strictly speaking necessary to run the tourbillon at that speed, and a slower rate of rotation can be advantageous for precision. A four minute tourbillon, for instance, puts a lower inertial load on the going train and mainspring than a one minute tourbillon; this allows you to use a weaker mainspring which reduces wear, and also reduces the amount of energy lost at the escapement as there is less inertia to overcome.

However, tourbillons today are as much about visual appeal as they are about precision. High speed tourbillons offer a little more drama. If you want to, though, you can make an argument for a higher speed of rotation on the precision side of things; the faster a tourbillon rotates, the less time it spends in any of the extreme positions. That’s the strategy behind De Bethune’s 30 second tourbillons, and also Greubel Forsey’s Tourbillon 24 Secondes.

Finally, there’s the question of craftsmanship. The tourbillon has lasted as long as it has partly thanks to what it can offer in terms of potential improvements to precision – for most of its history that was the primary and indeed, only real purpose of a tourbillon. The tourbillon fascinated watchmakers, and continues to fascinate them, for the scope that it offers for the exercise of craft, and not just craft for its own sake or as an end in itself. Tourbillons eat up a lot of energy. In a non-tourbillon lever escapement wristwatch, more than half the power from the going train is lost in the escapement alone (shocking but true). If you add a tourbillon, then the inertia of the cage and everything inside it – the balance, balance spring, escape wheel, and escapement – is added to the load on the going train.

A tourbillon, therefore, needs to be constructed with great care in order to work at all, and in order to have a reasonable power reserve. This means that tourbillon cages are general made of gossamer-thin steel, and the precision of all the other components – from the shape of pinion leaves, to gear teeth profiles, size and position of jeweled bearings, and the geometry of the escapement itself – has to be as great as possible. Yes, you can make a tourbillon watch that runs with mass produced components but generally such watches require excessively strong mainsprings. With tourbillons as with everything else in mechanical watchmaking, it’s not what you do as much as it is how you do it.

The Fascination Of The Tourbillon

So why is the tourbillon still so popular? Probably for the same reason mechanical watchmaking is still popular. Look at the history of the tourbillon. Patented in 1801, there were vanishingly few experiments with the basic concept for almost two centuries – an inclined tourbillon here, a flying tourbillon there, and that was about it. The tourbillon in many of the watches in which it was used, was not even visible; open dials showing off the tourbillon are a relatively recent development in watchmaking.

What did happen, however, was that like the mechanical watch, the tourbillon was freed by the development of quartz timepieces, from its slavery to practicality. In the late 1990s and early 2000s we began to see all sorts of interesting experiments that took the tourbillon far beyond anything A. L. Breguet might have thought of. Today we have multi-axis tourbillons, constant force tourbillons, inclined tourbillons, gyrating tourbillons, double tourbillons, quadruple tourbillons, the flattest ultra-thin tourbillons ever made – the list isn’t endless but it feels like it.

One wonders, though, if any brand today is brave enough to make a stealth tourbillon – one in which the tourbillon is not visible through an opening in the dial. Laurent Ferrier has some absolutely fantastic ones in his collections, including the Classic Tourbillon Ivory Enamel Grand Feu – one of the most discreetly beautiful tourbillon watches in the world, and in its discretion, a great rarity. Kari Voutilainen is also in the stealth tourbillon game; his Tourbillon with Chronometer Escapement will take your breath away if you have any breath in your lungs at all, and he’s even got a pocket watch stealth tourbillon in his catalog. (And if you want a tourbillon watch with a non-visible tourbillon, but with some astonishingly beautiful astronomical complications – and price is no object – has Patek got a watch for you).

In the last few years we have seen a major sea change in enthusiast tastes – smaller, classically styled watches with verifiably fine finishing, have been stealing collector’s hearts left and right (and for impressively large sums, to boot). I don’t think that there is ever going to be a wholesale rejection, either from collectors or from the industry, of visible tourbillons; they’re too much fun to watch. But the stealth tourbillon has its own appeal – an appeal to clarity and purity of design, and, as well, to the origins of the tourbillon in the pursuit of precision.

For more, check out our four part history of the tourbillon, The Tourbillon Chronicles: Birth Of The Tourbillon, Two Centuries Of Evolution, Rise Of The Tourbillon Wristwatch, and The Tourbillon In The 2000s.