Introducing The 1000 Hour Honoris I, From Haute Rive

Ulysse Nardin’s former Research and Innovation Director launches his first (amazing) watch.

Stéphane von Gunten’s name is not one you probably know unless you are a serious fan of modern complicated watchmaking in general, and of Ulysse Nardin’s complications in particular. A fifth generation watchmaker, he has spent most of his career at UN where he was involved in filing 30 patents, and worked on everything from the Moonstruck, to the Planet Earth Celestial Clock, to the Ulysse Nardin Anchor Tourbillon. He has struck out on his own for his latest project – a new, very high end company called Haute Rive, named after his great great grandfather’s workshop (von Gunten is the fifth generation of watchmakers in his family). The first watch from Haute Rive is called the Honoris 1 – a watch with a 41 day (1000 hour) power reserve, which is both very ingenious in its layout and very traditional in the amount of classical watchmaking craft that it delivers.

Generally speaking, making a watch with a very long power reserve, comes with unconquerable technical limitations. To run a watch with a power reserve close to or exceeding a month, you have no choice but to either use multiple mainspring barrels, or a smaller number of very long mainsprings. One pioneering example is the Jacob & Co. Quenttin vertical tourbillon, which set a world’s record in 2006, with a 31 day power reserve, which required seven mainspring barrels. The Lange 31 has two very long mainsprings, 1850mm in length each (according to Lange, about twice the length of a typical watch mainspring) and makes use of a train remontoire in order to even out the torque at the extreme ends of the power curve. Vacheron Constantin’s Twin Beat has an even longer power reserve – 65 days, but this is only if the watch, which has two oscillators, is in standby mode, using the balance that beats at just 1.2Hz. The watch with the longest power reserve ever, the all-time champion, is the Hublot La Ferrari, first delivered in 2013, which has a fifty day power reserve, seven mainspring barrels, and a case that looks as if it were inspired by Darth Vader’s helmet – to ease the strain on your fingers it comes with an electric screwdriver-like winding tool.

If however, you want something more aligned with classic watchmaking values and which doesn’t rely on the (ingenious) use of a second, slower running oscillator your choices are somewhat more limited and haute horlogerie complications, in the interests of both classical design and practicality, typically max out at about seven to ten days of power reserve. The Honoris 1, however, manages through some clever management of the going train, mainspring, and tourbillon carriage, to fit its 41 days of going time in a watch measuring just 42.5mm x 11.95mm, which is as small, or even smaller, than quite a few modern dive and sports watches.

Interest in long power reserve watches runs in the family. Irénée Aubry, van Gunten’s ancestor, was the inventor of an 8 day pocket watch movement, for which he received a patent in 1889. The patent was acquired by a watch company called Graizely Frères, which would eventually become Schild & Cie, and the movement was eventually sold in the famous 8 day “Hebdomas” watches.

The problem of housing a mainspring was solved in the Honoris I through the expedient of housing the mainspring in the entire diameter of the watch case. This solution was first used by Ulysse Nardin in the Freak, at the beginning of the 21st century but the idea is much older, going all the way back to the Waterbury Watch Company’s Waterbury Long Wind, which was patented in the USA in 1878 – the Long Wind had a nine foot mainspring and the entire movement rotated in the case once every 24 hours, making it, if you stretch the definition, a kind of tourbillon.

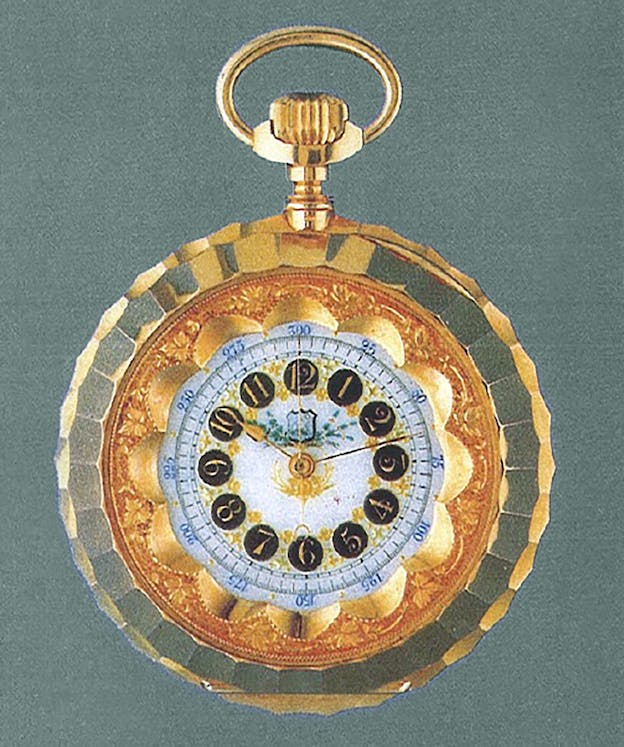

And rather astonishingly, there is another 40 day watch in Irénée Aubrey’s past. The watch was commissioned in 1887 for the Jubilee of Pope Leo XIII and was simply called the Montre du Pape, and it ran for forty days on a single winding.

If you try to wind the mainspring from the crown of the Honoris 1, you will be disappointed – the crown doesn’t wind the watch and it doesn’t pull out, either. Instead, you use it just for hand-setting and there is a crown wheel switching mechanism to select the hand setting function, actuated by a function selector at 2:00 in the case band. The column wheel is visible through a dial aperture at 2:00 as well. The stem extends all the way to the center of the dial where it gears to the motion works – somewhat reminiscent to me of the architecture of the original Lange 1, in which the keyless works were similarly located at the center of the movement, under the caliber L901.0’s central cover plate. The mainspring of the Honoris 1 is wound, like the Freak, by turning the bezel (the Freak however uses the bezel for both winding and setting the time).

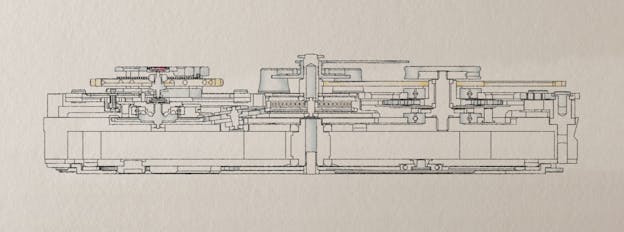

The watch is that it is built in two layers – the lower level houses the great wheel and mainspring barrel and everything else is elevated above the mainspring. This includes the ratchet wheel and going train, as well as the flying tourbillon carriage and differential system. Normally in a long power reserve watch, you would have the barrel and going train on the same level but this would require a thicker mainspring barrel and mainspring in order to deliver a long power reserve.

The watch is therefore something of a mystery watch in that key elements of the gears transmitting power are hidden from view, but this makes for an extremely elegant design – much more refined than you would expect from such a complicated watch. Despite the amount of time he has spent working with very high tech silicon components, von Gunten has produced a watch with very traditional materials and it is all the more impressive in that the Honoris I shows just how much you can do with classic watchmaking materials and methods.

The level of finish seems to be very high and appropriate to the ambitions of the watch overall and at a price at launch of CHF 148,000, the Honoris I seems to offer an enormous amount of real horological content, as well as an exercise in ingenuity from one of the most innovative minds in the business. Production will be limited to 10 watches per year. My first reaction to the Honoris I was of admiration for its technical chops but what I’m left with, at least for now, is of a high degree of technical innovation for which no sacrifices have been made in aesthetics.

The Honoris I 41 Day Flying Tourbillon: Cases, available in 18k white or yellow gold, with openworked grand feu enamel dials in white or black; 30M water resistance, 42.5mm x 11.95mm. Sapphire crystals, AR coated, front and back. Movement, HR01 caliber, hand wound via a rotating bezel with single mainspring barrel with 3 meter long mainspring; “mysterious” flying tourbillon rotating once per minute; lever escapement, variable inertia balance wheel; 38.45mm x 7.75mm, running at 18,000 vph in 35 jewels. All bevels hand finished in the traditional fashion with gentian wood from the Jura. Matching 18k gold pin buckles. Price at launch, CHF 148,000. For more info, visit Haute Rive online.