Greubel Forsey: The Masters of Invention

Symphonies in the key of the tourbillon.

Even by the rarefied standards of high end independent watchmaking, where obsessive attention to detail and highly personal visions of horology are the norm, Greubel Forsey is a watchmaker apart. The company makes only a small number of watches per year, and each one is dramatically different from anything any other company or watchmaker produces. Greubel Forsey is most famous, among collectors and enthusiasts, for its tourbillon watches – it has been in the forefront of innovation in tourbillon design since its inception – but the company has also created high complications, up to and including the grande sonnerie (a watch that chimes the hours and quarter hours) and a perpetual calendar with equation of time.

However, in horology as in so many other things, it’s not just what you do, but how you do it, and it’s here that Greubel Forsey really stands out (not that making multi-axis tourbillons isn’t a pretty good way to stand out to begin with). Greubel Forsey watches have that elusive but important ability to be instantly recognizable, even in bad light and across a crowded room. This is thanks in part to the overall size and design of the watches – they are visually dramatic straight out of the gate, with often ample-sized cases intended to give the watchmaking inside some breathing room. But is also due to the architecture of the movements themselves.

For much of the history of watchmaking, movements were hidden under dials and inside cases with solid case-backs – being able to see and admire a watch movement is something of a modern phenomenon, which is why you’ll see relatively few pre-quartz era watches with display backs. However, as mechanical watchmaking began to experience a rebirth after the so-called Quartz Crisis of the 1970s, interest in making an experience of the movement part of the experience of owning a mechanical watch began to rise.

Greubel Forsey watches take this fascination with watch mechanisms to its logical conclusion. It’s common for enthusiasts to speak of movement “architecture” but with Greubel Forsey, “architecture” is less a metaphor than a simple statement of fact. Their movements, which are generally clearly visible under the sapphire crystal, give the impression of being minute mechanical cities – rather than striving for flatness, for many years the standard goal of movement designs, Greubel Forsey calibers are resolutely three-dimensional, and the impression an owner has is of a self-sufficient mechanical world on the wrist. This aspect of Greubel Forsey watches, combined with the almost unbelievably high level of hand-finishing, has made Greubel Forsey watches famous among serious fans of ultra-high end horology from the very beginning.

Beginnings

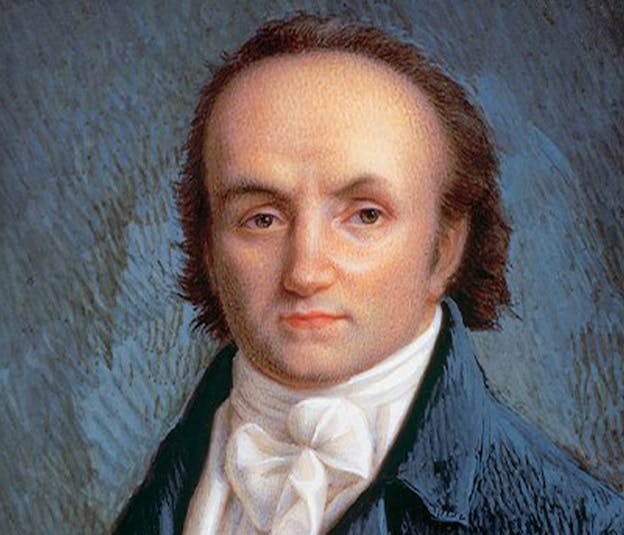

Stephen Forsey (left) and Robert Greubel (right)

Greubel Forsey is named for the two founders: Stephen Forsey, and Robert Greubel. Forsey, an Englishman, studied watchmaking at the prestigious WOSTEP (Watchmakers Of Switzerland Training and Educational Program) in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and then worked at Asprey’s in London in the restoration department, before going to work in Switzerland at the complications specialist, Renaud & Papi, in Le Locle (for many decades, one of the major centers of watchmaking in Switzerland). It was there that he met Robert Greubel, a French watchmaker from Alsace, who had come to work at Renaud & Papi after a stint at IWC where he worked on that company’s groundbreaking Grande Complication timepiece from 1990 – a minute repeater, perpetual calendar, chronograph watch, with a four digit year display for the perpetual calendar.

Renaud & Papi was, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, something of a finishing school for budding independent watchmakers. Greubel and Forsey were part of a larger group of young maverick horologists who would go on to have distinguished careers, including Andreas Strehler, the Grönefeld brothers, A. Lange & Söhne’s Anthony de Haas, and Carole Forestier-Kasapi (who designed what would eventually become the Ulysse Nardin Freak, and who is now Movement Director at TAG Heuer).

The company made it possible for younger, talented, imaginative and ambitious watchmakers to gain experience quickly in complicated watchmaking and in 2001, Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel left to start their own company – a complications specialist house called CompliTime. With the mechanical renaissance fully underway, as well as the era of the hyperwatch (an enthusiast’s catch-all term for major, talking-piece, high end complicated watches, the first of which was the Ulysse Nardin Freak) the duo thought it an auspicious time to launch their own brand as well. In 2004, Greubel Forsey launched its very first watch: the Double Tourbillon 30º.

A New Twist On The Tourbillon

The Double Tourbillon 30º was Greubel Forsey’s first attempt to solve a particular horological problem which has continued to command the company’s attention down to the present day. This problem has to do with the original problem which a tourbillon is intended to solve.

The tourbillon is not exactly ubiquitous, but it is more widely made today than at any other time in its history, and the visible, rotating tourbillon carriage is a mainstay – almost a requirement – of modern high end watchmaking. To not have a tourbillon in your collection, if you are an haute horlogerie brand, would be almost unthinkable and yet, most wristwatch tourbillons have not significantly updated the fundamentals of the design since it was invented.

The man who invented the tourbillon was the celebrated watchmaker, Abraham-Louis Breguet (today’s Breguet has been in operation, albeit through several ups and downs, ever since the founder established his workshop in Paris in the years just prior to the French Revolution.) Breguet was a restless and ingenious innovator, with many innovations to his credit but he is almost certainly best-known for the tourbillon.

One of the most basic problems in watchmaking is that a watch – unlike a clock – assumes various positions throughout the day. In Breguet’s time, pocket watches were generally in one of two basic positions – various vertical positions, in a pocket, or flat, when laid on a table at night while the owner slept. Thanks to the effects of gravity on the balance, balance spring, and escapement, the watch runs at slightly different rates in different positions, which in turn diminishes accuracy. Breguet’s insight was that if you put the actual timekeeping elements – the balance, spring, and escapement – inside a rotating cage, you would then have a single average rate for all the vertical positions. You would then only need to adjust the rate in the vertical positions to match the rate in the flat positions, and you should theoretically have a perfect timekeeper.

The tourbillon was very challenging to make for much of its history as the cage, thanks to its inertia, requires more power from the mainspring and therefore has to be as light as possible. The idea is sound, but it required a lot of skill from the watchmaker to fully realize the tourbillon’s potential. And, most importantly, the tourbillon as it was originally conceived, was intended for pocket watches – in a wristwatch, much of the advantage is lost as on the wrist, a watch is not just in either vertical or horizontal positions, but in a number of intermediate positions as well, all with slight variations in rate.

And this is where the Double Tourbillon 30º comes in.

The Double Tourbillon 30º is not, to put it mildly, a conventional tourbillon. There are two tourbillon cages, or carriages, instead of one – the inner cage rotates once every sixty seconds and the outer cage, once every four minutes (the traditional rate of rotation for a tourbillon is one minute but there are tourbillons with different rates of rotation – Breguet himself made four minute tourbillons, for instance). This is what makes the Double Tourbillon 30º a “double tourbillon” – the fact that it has two cages, one rotating inside the other, which turn at different rates.

But what really seals the deal is the fact that the axis of the balance is not (as is almost always the case not only in tourbillons, but in conventional watches as well) directly on the vertical axis of the movement. Instead, it is offset from the vertical axis by – you guessed it – thirty degrees.

The Double Tourbillon 30º is designed so that no matter what position the watch is in, the regulating organs are never in any of the most extreme positions for more than a moment. The greatest deviation in rate in a watch occurs between the perfectly flat and perfectly vertical positions, and since the tourbillon is never in either position for more than a fraction of a second, the most extreme rate deviations can be avoided. (Greubel Forsey were not the first to make a tourbillon with inclined balance – the American watchmaker A. H. Potter created one in 1860, but this was not a double tourbillon, though it’s an amazing piece of watchmaking nonetheless).

There have been wristwatch tourbillons before the Double Tourbillon 30º and going back further than you might expect – Patek, for instance, produced one in 1945 for the observatory chronometer competitions (the watch was cased in 1983 and worn by Philippe Stern as his personal wristwatch) and Omega also produced wristwatch tourbillons as early as the 1940s as well (a dozen or so, again, for the observatory competitions). But the Double Tourbillon 30º is the first tourbillon watch specifically designed for the conditions a wristwatch encounters in daily wear, and is therefore a significant watch, not just from an aesthetic standpoint, but in the larger history of watchmaking and horology as well.

The Double Tourbillon 30º is an extremely beautiful watch to see in action – the gyrations of the two tourbillon cages, one inside the other, is mesmerizing – but as with any mechanism intended to improve precision, the question is, “Does it work?” It’s extremely difficult to make blanket generalizations about tourbillon versus non-tourbillon watches, but it’s worth noting that in 2011, the Double Tourbillon 30º achieved the top score at the Concours de Chronométrie (a precision contest, which is now longer held) of 915 out of 1,000 possible points.

Design and Finishing

It often comes as a surprise to watch enthusiasts that, historically, one of the most significant distinguishing features of a high-end watch is something that in many cases, the owner will never see: movement finishing. Traditional movement finishing is done by hand, although it is possible to duplicate finishing techniques by machine as well.

The kind of movement finishing with which most collectors and enthusiasts are familiar, is the style which developed in Swiss watchmaking during the 19th and 20th centuries. Watch movements are made of basic materials: brass, steel, and jewels for the gears to run in. Hand-finishing a watch movement is not necessary functionally but it’s a big part of what elevates a movement from a machine to mechanical art.

True hand-finishing is extremely rare – it’s time-consuming, and requires watchmakers with years of training and experience. A Greubel Forsey watch shows the full vocabulary of high-end classic Swiss watchmaking finishing techniques. Plates and bridges have fully beveled and polished edges, and all steelwork is polished to a mirror-finish – mostly with a technique known as “black polishing” as the polished surfaces appear either uniformly black, uniformly white, or uniformly grey depending on the angle of the light.

The level of finishing in a typical Greubel Forsey watch is immediately obvious even to an untrained eye, and it extends to every part of the watch. Screws may seem a mundane component, but a screw in a Greubel Forsey watch is a miniature work of art in itself. A Greubel Forsey steel screw has a polished top, polished flanks, a polished slot, and the slot and screw head are beveled and polished as well. Some screws are individually heat-tempered to a cornflower blue, to contrast with the polished steel components and the frosted movement plates. Hand-finishing at this level is a vivid illustration of real luxury, in which it costs whatever it costs, and takes as long as it takes. And it does take time – at Dubai Watch Week 2019, Stephen Forsey told The 1916 Company’s Tim Mosso that on average, at that time in the company’s history, the hand-finishing for a typical Greubel Forsey watch required four and a half months of work hours. On Greubel Forsey’s movement architecture, Mosso says, “Most watches are built from the outside with a view to creating a distinctive vessel and then casing a range of movements to create model line. This is how most watches are built at independents such as Montres Journe, H. Moser & Cie., and Voutilainen. Greubel Forsey takes the opposite approach and builds its watches inside-out.

“Architecture rules at Greubel. Many brands polish ad infinitum, but Greubel and Forsey engage deeply with the mechanism to give it the qualities of a building. Each movement has depth, layers, and contrast. Even virtuoso movement finish from the likes of Philippe Dufour and Rexhep Rexhepi fails to overcome the packaging limits of classically thin dress watches. Messrs Greubel and Forsey don’t bother with that type of watch.”

One final note – the style of movement finishing in Greubel Forsey watches represents the heritage of both of the founders. While there are many elements of the Swiss finishing style, there are also many from the English classic finishing style, which made extensive use of frosted, gold-gilded movement plates contrasting with blued steel screws. The combination of the jewel-like glitter of the Swiss style, and the sober dignity of the English style, is another feature which sets Greubel Forsey watches apart.

Inventions and Models

The Double Tourbillon 30º was just the first in a long line of watches which are both major technical achievements, and platforms for exhibiting Greubel Forsey’s self-declared mission as a kind of living museum of traditional movement hand-finishing. Greubel Forsey watches at the most basic level are differentiated from each other by technical features, the various watch families that the company has launched over the years, and they reflect their creation of various watchmaking mechanisms with few if any direct precedents in historical watchmaking. Each of what Greubel Forsey calls its Fundamental Inventions can be found in a larger range of actual watch models.

Double Tourbillon 30º

The very first invention is the Double Tourbillon 30º, which is probably the single most iconic and single most recognizable invention. As we’ve said, the technical purpose of the invention was to experiment with adapting the tourbillon, which had originally been designed for pocket watches (and with good reason; the wristwatch, in Breguet’s time, did not exist except in rare instances when bracelet watches were made for women). With the balance tilted away from the horizontal axis, and with two periods of rotation for the inner and outer cages, the Double Tourbillon 30º was, although not the first wristwatch tourbillon, the first tourbillon designed specifically for the physical environment of a wristwatch. In addition to the first Double Tourbillon 30º one of the most memorable versions was the Double Tourbillon 30º Technique, which introduced Greubel Forsey’s signature architectural approach to movement design.

Quadruple Tourbillon

The second Invention is the Quadruple Tourbillon. The Quadruple Tourbillon is, as the Brits put it, just what it says on the tin – two Double Tourbillon 30º systems in the same watch. The rationale behind the Quadruple Tourbillon is exactly the same as that behind the Double Tourbillon 30º, but the pursuit of gaining every possible advantage over the effects of gravity on precision is taken to an even more narrowly fanatical level. The two double tourbillon systems further increase the averaging effect of the original double tourbillon system and to get even more of an edge, one of the two double tourbillons in the Quadruple Tourbillon is inverted, so that the balances are offset not only from the horizontal plane of the watch, but also from each other. The rates of the two tourbillon systems are averaged by a differential mechanism to produce one rate more stable than either system alone.

And, if you’re looking for a Greubel Forsey watch which represents both further refinement of the tourbillon for a wristwatch, and a powerful statement of Greubel Forsey’s aesthetic vision, you could hardly do better than Invention Piece No. 2, which showcases the Quadruple Tourbillon in a most dramatic way – or the even more visually stunning Quadruple Tourbillon GMT, with its two double tourbillon systems and miniature globe of the Earth, rotating once every 24 hours.

Tourbillon 24 Secondes

The third invention is the Tourbillon 24 Secondes. If the history of watchmaking has taught us anything it is that there is more than one way to skin a cat, and while we think of mechanical horology nowadays as inherently tradition-bound and conservative, its history has actually been conservative only insofar as it’s necessary to preserve key fundamental tech – there are, for instance, probably hundreds of different escapements which have been tried out in the last five centuries. So it is with the Tourbillon 24 Secondes.

The Double and Quadruple tourbillons are experiments in rotating the regulating system through as wide a range of positions as possible in order to avoid the effects of the most extreme (perfectly flat or perfectly vertical) positions. The Tourbillon 24 Secondes, on the other hand, is mechanically a much simpler system and takes perhaps a more direct approach. While the double and quadruple tourbillon mechanisms used a highly complex system of nested tourbillon cages and (in the case of the quadruple tourbillon) differentials, the Tourbillon 24 Secondes uses a single tourbillon, inclined at 25º but rotating very fast, at one rotation of the cage every 24 seconds. While the solution is very different from the double and quadruple tourbillons, the basic rationale is the same – only in this case the tourbillon is rotating so quickly that the chances of it spending any significant time in any of the extreme positions is essentially zero.

Balancier Spiral Binôme

The fourth invention is the Balancier Spiral Binôme. This is the one invention which has never, as far as I know, been used in an actual production watch (from Greubel Forsey or anyone else). Greubel Forsey explains it: “The Balancier Spiral Balancier Spiral Binôme, our fourth Fundamental Invention. In order to improve the interaction between the balance and the balance spring, we explore the use of the same material for both components – a material which would be impervious to temperature variations and nonmagnetic in order to exploit its physical properties for the balance and the balance spring.”

Différentiel d’Égalité

The fifth Invention is the Différentiel d’Égalité. The Différentiel d’Égalité addresses a different problem than previous Inventions, which were designed to reduce the effects of gravity on the precision of a wristwatch. This problem is that of energy delivery to the balance. All watches are driven by a mainspring – a spiral spring whose coils tighten when you wind a watch, and which power the gear train as the mainspring unwinds. The problem is that the mainspring tends to deliver too much power at full wind, and not enough as it reaches the end of its power reserve. This can be addressed by including a mechanism known as a remontoire, which is essentially another, smaller mainspring placed in the gear train, which is periodically wound by the mainspring.

As the remontoire is rewound frequently – F. P. Journe uses a one second remontoire, although the interval can be anything from a second, to minutes – it provides a steadier supply of energy. However, there are still spikes in power every time the remontoire is rewound and to address this, Greubel Forsey added a differential system to its one second remontoire, to average out the peaks and valleys in energy delivery. The Différentiel d’Égalité was incorporated into a watch of the same name, released in 2018.

Double Balancier

The sixth Invention is the Double Balancier. The Double Balancier represents another technical solution to the problem which the tourbillon is designed to address, but the strategy is slightly different. The Double Balancier is not a tourbillon watch or a double tourbillon watch, but it does have two balances – the balances are both inclined at a 30º angle. They are also angled in different directions, and the idea is that if one balance happens to be closer to one of the extreme positions (perfectly horizontal, or perfectly vertical) then its rate variation will be to some extent, canceled out by the other balance. The two balances are linked through a differential mechanism, which produces a single rate that is the average of both balances, and the system can be seen in the Double Balancier Convex.

Le Computeur Mechanique

The Seventh Invention is Le Computeur Mechanique, which can be seen in the QP à Équation – a perpetual calendar wristwatch with an indication for the Equation of Time. The watch also has a tourbillon, inclined at a 25º angle. The “Computeur Mechanique” is a system of stacked gears which encode the information for the perpetual calendar, including the length of each month, as well as the leap year change in the length of the month of February (during which February has an extra day added – February 29th). The Equation of Time is an unusual horological complication, which shows the difference between mean solar time and apparent solar time. The easiest way to understand the complication is that it shows the difference between the time you’d see on a sundial and the time you’d see on a clock – the length of a day as shown on a sundial will vary slightly throughout the year, thanks to variations in the Earth’s orbit as well as the tilt of its axis, while a clock shows the averaged length of a day (24 hours, every day).

The Computeur Mechanique drives a system of sapphire disks which show both the Equation of Time and the month, and the watch has a four-digit display of the year as well – both visible on the back of the movement.

Grande Sonnerie Minute Repeater

Although it’s not one of the fundamental Horological Inventions, it’s worth noting that Greubel Forsey has also produced a chiming watch – the Greubel Forsey Grande Sonnerie Minute Repeater. A Grande Sonnerie Minute Repeater is a watch which can chime the hours, quarter-hours, and minutes “on demand” (the minute repeater part of the complication) but which can also chime the hours and quarter hours “in passing,” like a chiming clock.

Other Significant Models

It’s a little odd to select “significant” models from Greubel Forsey as production numbers are so low. At any given point in its history, the company produced only one to two hundred watches, which means roughly one to two watches per employee – an extremely exclusive number no matter how you slice it. However, there are certain specific models which will stand out to any collector or connoisseur, and The 1916 Company’s Director Of Media, Tim Mosso, has been able to handle and experience perhaps more Greubel Forsey models than anyone outside of the company itself. Here, he shares his favorites and his views on their significance to both the company’s history, and to collectors – there are of course, classic models like the Double Tourbillon 30º but there are also less well know models like Art Piece 1, which is a showcase for a nearly microscopic sculpture (and which has a built-in microscope in the case) and Hand Made 1, which is that extreme rarity, a watch made only with traditional hand-operated watchmaking tools.

Double Tourbillon 30º

“The original 2004 Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon 30° is a landmark watch that remains the brand’s most emblematic. It embodies everything that makes Greubel Forsey watchmaking special. More than just another giant tourbillion amid a decade drowning in them, the DT 30° was a serious attempt to re-engage with the chronometric intent of Abraham-Louis Breguet’s late eighteenth-century vision. And the DT 30° delivered. This model won its class at the 2011 Concours International de Chronométrie, a rare timing-precision showdown in an industry that generally avoids the potential embarrassment of accuracy-oriented acid tests.

For good measure, the DT 30°’s innovation was packaged with savant-level attention to decoration. Pocket-watch inspiration was evident in the gilded bridges, traditional materials such as maillechort, and oversized blued screws. Comparably innovative watches from the likes of George Daniels and “pre-Montres” François-Paul Journe often lacked more than rudimentary attention to decorative finishing. But Greubel Forsey declared that for the right price, you could have it all.

2007 brought my favorite version of the Double Tourbillon 30°, the “Secret.” While dimensionally and technically identical to the 2004 original, the DT 30° Secret harked back to a time when discretion was a selling point and classical brands such as Patek Philippe and Jaeger LeCoultre hid their tourbillons beneath solid dials. In some ways, an invisible Greubel Forsey tourbillon is as antithetical to the brand ethos as a Panerai WITH a tourbillon is to that combat-spawned label. But the solid-dial DT 30° holds sway in my heart, and I’m in good company; Stephen Forsey told me that the Secret was one of Robert’s best design efforts.”

DT 30° Secret

“2007 brought my favorite version of the Double Tourbillon 30°, the “Secret.” While dimensionally and technically identical to the 2004 original, the DT 30° Secret harked back to a time when discretion was a selling point and classical brands such as Patek Philippe and Jaeger LeCoultre hid their tourbillons beneath solid dials. In some ways, an invisible Greubel Forsey tourbillon is as antithetical to the brand ethos as a Panerai WITH a tourbillon is to that combat-spawned label. But the solid-dial DT 30° holds sway in my heart, and I’m in good company; Stephen Forsey told me that the Secret was one of Robert’s best design efforts.”

Tourbillon 24 Secondes

“The 2008 Tourbillon 24 Secondes proved that fewer tourbillons didn’t mean less appeal. As part of a pioneering generation of “fast” tourbillon wristwatches, the dynamic 24 Secondes was a milestone watch for the Greubel Forsey brand and the greater watch industry. The frenetic 24-second circuit of its double-step heartbeat returned to win the 2015 GPHG Aiguille d’Or as the visually stripped-down Vision 24 Secondes.”

Quadruple Tourbillon

“As if to pitch a riposte to its own 24-second single tourbillon, Greubel Forsey’s next major launch was the 2009 Quadruple Tourbillon. It was a festival of excess. As an icon of the late 2000s, it was simultaneously iconic and ironic. As a clock, the “Quad” would have been a peerless achievement. As a watch, the best case for the four-tourbillon machine is that it’s more practical than wearing four separate tourbillon watches.

The moment for watches like this had passed by early 2009’s post-Lehman juncture, and the insane multi-heart flagship became a sort of 1959 Cadillac for the wrist. Each was the ultimate embodiment of an era, and each arrived just past that era’s apex. With four tourbillon regulators linked by a differential to average their rates, the Quad’s 531-component movement was both a monument to excess and a baroque solution to minimizing the effect of gravity on a mechanical watch. Far from chastened by changing economic tides or tastes, Greubel Forsey persisted with the concept and relaunched it with a GMT function in 2019.”

Tourbillon GMT

“Greubel Forsey evolved as a brand even as it clung longer than most to the monumental design vernacular of the 2000s. 2011 saw the world still beset by sputtering commerce, but the Tourbillon GMT anticipated better times to follow.

And nothing anticipates a global recovery like a watch that packs its own globe.

Resplendent in titanium, the Greubel globe doubled as a world time display for owners with a visual imagination sufficiently strong to project meridians onto the marble-like rendition of Earth. A more intuitive world time display on the caseback delivered easier reading and setting. And for those who dream in black and white, a conventional second time zone pulled yeoman duty on the dial side.”

Art Piece 1

“2013’s Art Piece 1 flew in the face of the horological “métiers d’art” conventions; this watch nearly amounts to a send-up of the craft arts genre. Rather than showcase a legacy skill such as gem-setting or enameling, the Art Piece 1 served as a mini-vitrine for—among others—a micro sculpture of a three-masted galleon, in gold, by Britain’s Willard Wigan. Greubel Forsey has a knack for combining frankly weird ideas in packages that launch with no obvious market or client, and that takes courage.

This is a polarizing watch. “Nano-sculptures” and integrated microscopes have no natural link to horology, and the AP1 is, in truth, a gimmick. But I subscribe to the notion that two virtuoso works of art are better than one, and I enjoy the implicit irony of a huge watch that contains a tiny sailing ship.

Despite the skepticism with which some watch collectors regard the Art Piece 1, it’s probably the watch that evoked the most unalloyed joy from non-collectors in my marketing and finance departments. Absent watch snobs, the AP1 and its micro gallery were a huge hit.”

Signature 1

“The 2016 Signature 1 was a milestone Greubel Forsey for two reasons. First, the collaboration with the company’s own Didier Cretin reflected growing interest in empowering individual creative visions of traditional watchmaking. That was one key quality Greubel Forsey hoped to promote via the contemporaneous “Naissance d’une Montre” program sponsored by Greubel, Forsey, and other watch industry majors.

Second, the simplicity of the time-only Signature 1 made it the vanguard of a new generation of more restrained GF products that arrived in the late 2010s. After the Signature 1, Greubel Forsey launched a succession of watches with smaller cases and reduced complexity; the trend continues as of 2022. The 2017 Balancier, 2019 Balancier Contemporain, and the 2020 Balancier S sports watch all trace their roots to the breakthrough simplicity of the Signature 1.”

Hand Made 1

“Greubel Forsey’s 2019 Hand Made 1 is a sobering watch; it can rattle the cages of collectors who assume that six and seven-figure price tags assure handmade status. True, manual labor is more prevalent at Greubel Forsey than at most watch brands. But the company still depends extensively on automation including CNC, electro-spark-erosion, and LIGA to hit its 2022 production target of 150-200 timepieces. A $1 million Hand Made 1 departs La Chaux-de-Fonds two or three times per year.

My time with this was illuminating; many of its sub-assemblies are assembled from components rather than machined as units. There are many seams where the tourbillon cage comes together. This is the consequence of craftsmen working exclusively with hand tools.

While the stones and sapphires are sourced from suppliers, almost everything else on HM1 is fabricated and finished over a purported 6,000 human-hours – and I believe that claim. The case, bridges, and tourbillon of the HM1 are less elaborate than on Greubel Forsey watches that cost half the price. This watch will never be a profit center for the brand, and I adore the Hand Made 1 for the simple fact that it exists.”

The Future of Greubel Forsey

As of this writing Greubel Forsey’s CEO, Antonio Calce, has said that moving forward the company will have a dual strategy. It will continue to produce no-holds barred, cost-is-no-object hyperwatches like the Quadruple Tourbillon, but the company will also produce watches which, while mechanically less complex, are still made to the same uncompromising level of quality. The latter will be produced in somewhat larger numbers than Greubel Forsey’s previous output – for most of its history, about 100 watches a year – with the goal to eventually produce as many as 500 watches per year total. This includes watches such as the Balancier S Convexe, as well as the 2022 GMT Balancier Convexe.

If the Balancier series of watches are any indication, the fundamental appeal of Greubel Forsey watches will remain the same as the company evolves. That appeal is now and will always be based on the celebration of the movement as both a technical and visual tour de force. Tim Mosso puts it well: ” A person looks at many fine movements; one can get lost in a Greubel Forsey.”