The Art Of Invention: How De Bethune Builds The Future Of Watchmaking

At De Bethune, technical innovation and horological art go hand-in-hand.

There is a natural tendency when you look at watches, to think of aesthetics and mechanics as separate enterprises – the watchmaker’s art is not the casemaker’s art is not the dial-maker’s art, and so on. And for a lot of the history of watchmaking that was such a natural way to look at watches, that it never really occurred to anyone to think otherwise. George Daniels once wrote that looking at the movement, much less admiring it, would have been beneath the dignity of a client, as such things were matters for tradesmen, not gentlemen.

How times have changed. It’s not exactly a universal sentiment that movements can and should be beautiful – nobody buys a Rolex to admire the movement (except maybe the new 1908) but for a lot of connoisseurs and collectors, the movement had better be up to snuff or the watch is of no interest. Ubiquitous macro photography on the Internet, showing movement components up so close you’d have to be a microbe to see what the picture shows, are endlessly argued over, and whether or not Geneva stripes are done properly, or sharp internal angles present where they should be, are matters discussed with all the passion and partisanship of wine enthusiasts debating the merits and flaws of a premier grand cru. Understanding and appreciating traditional movement finishing has become, at least to some extent, de rigueur for anyone who wants to be considered a serious collector.

When Essentials Become Essence

However, this fundamentally doesn’t change the dichotomy between aesthetics and mechanics, and even in the most elevated hand-finished watch, the case and dial, while usually made with great care and often with as much investment in traditional craft as the movement, are still separate in our minds from the movement. They’re static components, essentially a frame – a beautiful frame, and for sure one with a practical purpose (nobody wears uncased movements on their wrist) but a frame nonetheless – a vessel for presenting the time and protecting the movement.

At De Bethune, not only are the technical aspects of a watch on a continuum with the aesthetics, but those technical features are themselves the subject of iterative evolution and are often so far removed from conventional solutions that they become an integral part of the aesthetics – on-stage in starring roles, rather than working behind the scenes.

Take for example, the balance wheel, balance spring, and the anti-shock system. The pioneering watch writer Walt Odets once wrote that “a watch has no extra parts” – in other words, every part is essential. However, these three components are in a very real sense, the heart of a watch. Generally, though, you would be very hard pressed to tell the difference between a balances in a one hundred dollar watch and a one hundred thousand dollar watch – the craziest things usually get is the use of a freesprung balance and overcoil instead of a standard regulator and flat balance spring. And anti-shock systems? If I had a nickel for every time someone’s said, “wow, what a beautiful anti-shock spring” – well, I pretty much wouldn’t have any nickels.

Technical Perfection And Watch Aesthetics

De Bethune, on the other hand, has been thinking outside the box from a technical standpoint, since at least 2004, which is when Denis Flageollet introduced a number of innovations which in one form or another have been part of the company’s technical and design language ever since.

In 2003-2004, De Bethune began rolling out technical updates to these basic elements of watchmaking that were anything but basic. One of them was at least to an untrained eye, a little mundane – this was a balance spring, still used by De Bethune today, which has a sort of secondary outer terminal curve that does what a Breguet overcoil does, but in a flat spring (the outer terminal curve also acts as a shock absorber). The main advantage here is a reduction in height – a standard Breguet or Phillips overcoil adds to the overall thickness of a movement, which is why you won’t find them in ultra-thin watches.

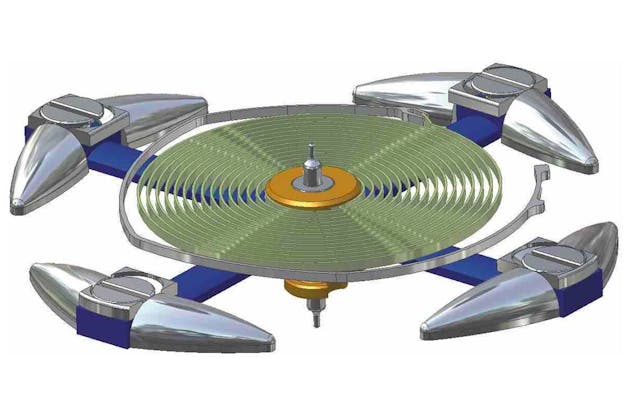

The technical updates to the balance, however, produced some of the most beautiful and exotic-looking components in the history of modern watchmaking. Denis Flageollet’s balance designs had improvements in practical watchmaking behind them, but, not coincidentally, they also looked extremely cool. The basic idea was to see what could be done to improve the physical characteristics of the balance, by placing as much mass at the periphery as possible, and also to improve aerodynamics.

The pace of evolution was pretty breathtaking. The first of the new generation of balances looked less like a traditional balance, and more like something you’d expect to see above Area 51 – there were four smooth oval weights, made of platinum, mounted on four titanium arms, and the platinum weights could be moved inwards or outwards on their arms in order to fine-tune the rate of the watch. This design was followed in rapid succession by a half-dozen more, and the basic principles behind the first De Bethune in-house balance are still present in the latest versions.

The goal was not to make a balance proceeding from design principles first, but it sometimes happens that pursuit of a technical goal in mechanics can lead – almost inevitably, in some cases – to a beautiful final result, and that’s the case with De Bethune’s in-house balance systems, which, thanks to their optical properties, colors, and physical configurations, become an integral part of the watch design overall. One detail among many is that the use of blued components in combination with polished white metal surfaces is a constant theme in many De Bethune watches – something found in both the De Bethune balances, and in the triple pare-chute anti-shock systems.

De Bethune’s anti-shock system – the so-called “triple pare-chute” system (the name is derived from Breguet’s pare-chute antishock mechanism) is another example of pursuing functionality to such a logical extreme that it becomes an aesthetic in its own right. The triple pare-chute system starts with a conventional anti-shock spring for the balance pivots, but it also includes a balance bridge, extending out to either side of the balance, which is in turn secured under two additional anti-shock springs with an elongated S-shape. The system is technically advanced – it provides additional protection against damage, but it also improves chronometry by returning the balance to a centered position after any physical shock.

The triple pare-chute system is one of the single most distinctive design elements in De Bethune’s watches. We conventionally separate mechanical innovation in watchmaking from design innovation but the reality at De Bethune is that design history and technical innovation go hand-in-hand. It’s a signature feature that demonstrates one of the most fundamentally appealing aspects of watchmaking – the ability of the pursuit of functional excellence to produce unexpected beauty.