A Patek Philippe 5270G-014 Perpetual Calendar Chronograph

An historic reference, a modern watchmaking masterpiece – and a little controversy too.

In a Leap Year, naturally, a young (or in this case, a rapidly aging) man’s fancy turns to the thought of perpetual calendar wristwatches and their infinite variety, and as nature takes its inevitable course, to the thought of Patek Philippe. The company has over the course of its nearly two centuries in business, shown a mastery over the generations of every kind of complicated watchmaking imaginable. However there is perhaps no complication more associated with Patek than the perpetual calendar, which Patek began making in 1941 with the 1526. Just as well known are its perpetual calendar chronographs. Patek began making them in 1941 as well, when it introduced the 1518, and the company has been in the perpetual calendar chronograph business ever since. Over the years and up to the present, there have been a number of different references which are by convention divided into series, depending on the date of introduction and variations in design, and so every perpetual calendar chronograph from Patek has a story to tell.

By definition, every Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronograph is historically important but one of the most significant, and a model which saw some major technical breakthroughs as well as a number of updates to previous designs, was the 5270, first introduced in 2011 and still in the current catalogue. The 5270 is larger at 41mm by a small margin than Patek’s next largest modern perpetual calendar chronograph, the rattrapante chronograph perpetual calendar 5204, which comes in at 40mm. Aside from the rattrapante chronograph function the main difference between the two is the tachymeter scale on the 5270, but both represent the state of the art in modern, lateral clutch chronographs.

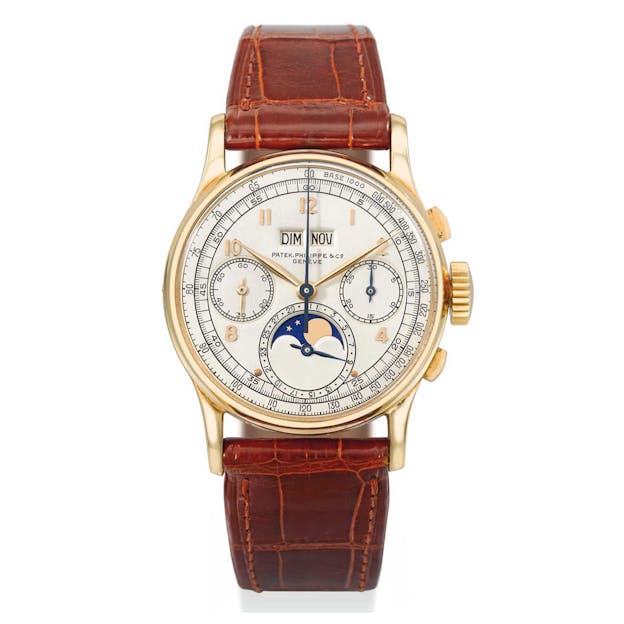

The 5270 we have here today is the 5270G-014, in white gold.

The 5270 has been introduced in several different series (it’s currently available in yellow gold, rose gold, and platinum) and when the first series was introduced, it was without the tachymeter scale which had been present on its immediate predecessor, the 5970, which had launched in 2004 and which at that time was the first Patek Philippe designed by Thierry Stern, who is the fourth generation of his family to lead the company. The presence or absence of a tachymeter scale is one of the main design elements distinguishing one Patek perpetual calendar chronograph from another and if you look at the entire series production (as you can in this classic reference article from Revolution’s Wei Koh) you can see the tachymeter scale appearing and disappearing from one series to the next – it was present on the 1518 and the first two series of the 2499, but omitted from the third and fourth series. The tachymeter scale was also absent on the 3970 which was sold from 1985 to 2004 (except for one unique piece made for Eric Clapton).

The inclusion of a tachymeter scale represents a design problem with several possible solutions. The problem is that the chronograph seconds scale and tachymeter scale are concentric and therefore the subdial for the date, especially if the date numbers are large enough to be reasonably legible, is going to cut at least into the innermost scale. In the 1518, the date numerals cut into the seconds track but not the tachymeter scale and the numerals on the tachymeter scale are a little on the small side (as are the date numerals – perhaps people had better eyesight in those days, or maybe optometry has gone downhill since 1941, which seems less likely).

You can get around this by putting the tachymeter scale on the bezel, as in the Omega Speedmaster (an apples to oranges comparison of course; for one thing, the Speedmaster is not a perpetual calendar) but the logic of doing so would still apply here were it not for the fact that of course, with a tachymeter bezel you have a watch with a totally different character.

Before getting to the tachymeter scale, though, let’s talk movements. Of course, Patek would not be Patek if the designs were not first and foremost balanced, subtle and elegant, and while I think it’s true that every watch to some extent lives or dies by its details, it’s especially true of Patek. You could write a book just on the lug variations in Patek perpetual chronos (or at least, a very long article). However it is also true that in another sense, Patek is really all about movements. For much of the history of Patek Philippe, the company used highly modified Valjoux, and then Lemania, chronograph calibers but it became increasingly obvious to Patek that ideally, it would rely not on suppliers but rather on its own manufacturing capability. This would enable it to create chronograph movements better suited to support complications like a rattrapante mechanism and perpetual calendar as well.

The 5270 introduced the caliber CH 29, which is a lateral clutch, column wheel controlled hand-wound chronograph (in contrast to the CH 28-520 which preceded it, which is a vertical clutch automatic chronograph with a single subdial for elapsed hours and minutes). While this is a very classically laid out caliber at first glance, it is nonetheless a real departure from its supplied predecessors and the design was awarded a total of six patents. These include:

- An optimized tooth profile for the chronograph intermediate driving wheel and chronograph center seconds wheel, to prevent jumping of the chronograph seconds hand when the chronograph is started

- Improved coordination of the chronograph brake lever and chronograph clutch lever

- Improvement in adjusting the depth of engagement of the driving wheel and chronograph center seconds wheel (via the column wheel cap)

- Improvement to the minute counter wheel to reduce friction when the minute counter jumps

- Self-adjusting reset hammers

- Jeweling for the reset hammer pivots

The last major difference between the CH 29 and the Lemania caliber CH 27 that preceded it is in the balance frequency – CH 27 oscillates at 18,000 vph, vs. a modern 28,800 vph for the CH 29.

One other point worth noting, because it’ll come up again in a minute, is that the design of the movement puts the center of the small seconds dial and the chronograph minutes register, slightly below the horizontal axis of the dial.

The 5270 represents another major milestone as well. The CH 27 was stamped with the Geneva Seal, which was and is a standard administered by the City and Canton of Geneva, and which is both a mark of provenance and a set of quality standards for watch movements. In 2009, however, Patek introduced its own internal standard – the Patek Philippe Seal, which unlike the Geneva Seal contains standards for the entire watch as well as the movement, and also establishes performance criteria (one interesting stipulation from the Patek Seal is that all tourbillons must have a maximum deviation in rate of +2/-1 second per day, which is a much tighter spec than the COSC spec for chronometers).

What really sells the movement, though, is its sheer beauty. The finishing is up to at least the standard of anything that Patek did with the CH 27 and if what you’re looking for is a technically up to date version of the classic highly finished and fine-tuned Lemania chronographs of yore, this is I think as good as it gets. This would be a fascinating movement to watch in operation, especially with a little study of its technical features.

Now, going back to the dial side, let’s take a look at a couple of new features characteristic of the 5270 and also one feature specific to the second series.

First of all, you’ll notice that there are two apertures on either side of the date/moonphase subdial. The one on the right is the Leap Year indication. The first Patek perpetual chronograph to have one was the 1985 3970, which showed the Leap Year via a hand in the same subdial used for the running seconds. Here, for the first time, Patek has used a window. The window to the left is a day/night indicator, which is useful when setting the calendar – for one thing it helps you avoid accidentally trying to change the calendar when it’s in the middle of switching over at midnight; doing so may damage the mechanism.

Then there is the date indication itself. The Roman numerals are noticeably larger than in earlier references like the 1518 and 2499 and this is both a concession to legibility, as well as a design choice – the larger typeface makes for a more assertive look. If you look closely you’ll see that the numbers are so large that they barely clear the subdials – in fact the 5 and 27 are both visibly shorter than the numbers next to them. There is a little bit of a visual illusion, thanks to the size of the font, that the numbers are closer together as you get into the double digits but the angular distance between the center of each number is the same (it would have to be unless the teeth on the date wheel were unevenly spaced).

And finally, there is what enthusiasts have nicknamed, “The Chin” – this is the curvature of the tachymeter/seconds scale as it rounds the underside of the date window. This partly has to do with the fact mentioned earlier, that the centers of the minute and small seconds subdials is below the horizontal axis of the dial – everything is shifted downwards slightly, in comparison to the Lemania and Valjoux based chronographs that preceded the 5270 – and is also partly due to the decision to use a larger font for the dates.

The Chin was something of a divisive feature, and in subsequent series of the 5270, Patek went back to the more traditional solution, which is to have the lower subdial simply cut off part of the tachymeter/seconds track. This however means that the second series 5270s are relatively rare as they were produced for just two years – 2013 and 2014.

Like many designs that were considered niche, idiosyncratic, or even weird when they were first launched (the Royal Oak springs immediately to mind) the second series 5270 seems to have grown on collectors since it was discontinued (and of course, there’s nothing like discontinuing something to make it immediately more attractive). The Chin sticks out – well, like a chin, and it’s certainly for good or bad a distinguishing feature of the reference. I like it though. Perfect symmetry is great but it can get a little tiring and even become uninteresting. The Chin on the 5270 kind of reminds me of Marilyn Monroe’s famous mole; and one man’s mole is another man’s beauty mark. Between the historical importance of the reference, the technical features of the CH 29 and its great beauty, and the distinctive design of the dial, I think this particular series of the 5270 is one of the most fascinating in a long line of fascinating perpetual calendar chronographs from Patek Philippe.