A Breguet “Souscription” Pocket Watch, From The Master Himself

“To carry a fine Breguet watch is to feel that you have the brains of a genius in your pocket.”

Sir David Salomons, the single greatest Breguet collector of all time, whose collection included the notorious “Marie Antoinette” super-complication, made this remark about Breguet in his book, simply entitled, Breguet, in 1921. (His collection, after his death, ended up by a very circuitous path, at the L. A. Meyer Museum Of Islamic Art in Jerusalem, where a daring thief, working alone, stole the Marie Antoinette and dozens of other irreplaceable Breguet clocks and watches. The watches were eventually recovered, but not before the late Nicholas G. Hayek had Montres Breguet make a perfect reproduction of the original, from Breguet’s original drawings).

Breguet enjoys a reputation unlike that of any other watchmaker, living or dead. The factors which led to his enduring legacy probably cannot be repeated; he was a true pioneer in the pursuit of innovation in both precision timekeeping, and ingenuity in complicated watchmaking, and while he is most famous for his invention of the tourbillon (there is however, some reason to think that he may have at least co-invented the tourbillon with John Arnold – after two plus centuries, though, settling this question definitively may be impossible) the list of his innovations and improvements to watchmaking as it existed during his lifetime extends far beyond his mechanical “whirlwind.”

One of Breguet’s most important innovations was the creation of the watches known as “souscription” or subscription, timepieces. Breguet had observed that if no expense was spared, that it was certainly possible to create extremely precise timepieces and his “garde-temps” class watches and exotic high precision clocks, which were made one at a time, were marvels. These were usually made for extremely wealthy clients with a specific interest in the physical sciences in general, and precision timekeeping in particular.

The problem was that they were marvelously expensive, too, and Breguet, having survived the French Revolution by decamping to Switzerland (his birthplace) and then London, returned to Paris to find a Republican government in place, and a burgeoning bourgeois market for high quality, precise watches, which no one was filling. He therefore hit upon the idea of creating a mechanically robust, simple watch, which would offer excellent precision but not break the bank. This idea was behind the genesis of his Souscription watches, which could be purchased with a down payment of 25 per cent of the total price, the balance payable upon delivery.

Prices ranged from around 600 francs, up to 800 francs or so depending on case materials and engraving. About 700 of them were eventually manufactured (it’s often said, erroneously, that Breguet personally made all the watches that bear his name – he had, in fact, a substantially staffed workshop and was well-liked by his workmen and watchmakers for the generous terms of employment).

For this week’s edition of A Watch A Week, we have what I think is one of the most exciting watches I’ve ever had a chance to handle during my tenure at The 1916 Company (now, of course, The 1916 Company). The watch we’ve got for you today is a Breguet Souscription, but a somewhat unusual one.

This is Breguet No. 1602, which was sold on the Revolutionary calendar date of 6 Fructidor, Year 13 (August 24th, 1805; the Republican government in its desire to be modern and reject the trappings of the Ancien Régime, had instituted a new calendar based on a twelve month year, with each month broken into three weeks of ten days each. Even by the very low standards of attempted calendar reform, it was an unpopular disaster and the government killed it off after just 12 years). The watch is a very large, imposing and impressive timepiece, 61mm in diameter, with a gold case, gold dial, and Breguet’s own version of the cylinder escapement. Like all Souscription watches, No. 1602 has a single hour hand, with no minute or seconds hand but the dial is large enough, and the tip of the hour hand fine enough, that the time can easily be read to at least the nearest five minutes (the dial is marked off in five minute increments between each hour). With better eyesight than mine (Kids! The word of the day is “presbyopia!”) you could probably read it off to the minute.

The fact that this was, essentially, a starter watch for Breguet did not mean that he was cutting any corners. In fact, this particular watch was sold to a client – a Monsieur Frédéric Frackmann – who’s known to have bought at least two other watches (both repeaters). Breguet’s archives describe him, in the sale notes for one of the repeaters, as “Monsieur Frackmann in Moscow,” so the watch might have been intended for resale in the Russian market. Certainly the engine turning for the case and dial are exceedingly opulent and the precision with which all the work was done – with hand tools – is impressive. The nonfigurative geometric motifs manage to exude both opulence, and dignified restraint, at the same time, which is very difficult to do (ask the man who’s tried).

The original announcement for the Souscription watches doesn’t say anything remotely like “Come on down to 51, quai de l’Horloge in the Île de la Cité for watches priced so low we’re practically GIVING THEM AWAY!” Instead, the Notice said that the watches were suitable for “Astronomy and the Navy,” and were also designed to be as watchmaker-friendly as possible, with a relatively low number of strong, well-made components. The Souscription watches were fitted with some features Breguet had already introduced in much more expensive chronometers (including his tourbillons) and featured his pare-chute antishock system, as well as temperature compensation for the carbon steel balance spring.

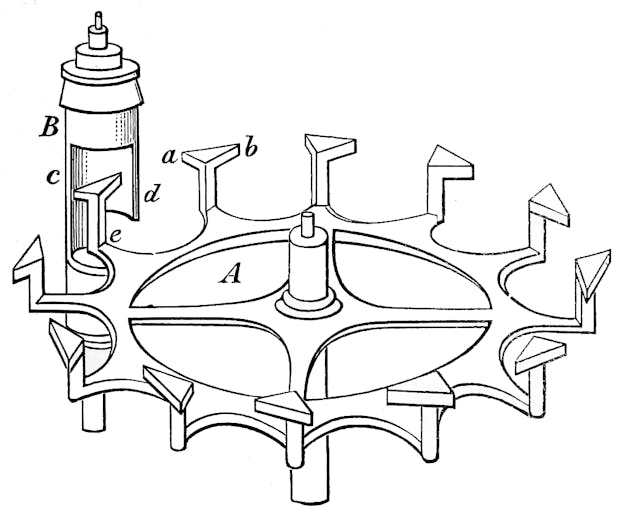

An additional refinement, hidden under the dial, is the Maltese cross stopworks, which prevent the mainspring barrel from winding down completely; this ensures that while the watch is running, only that part of the power reserve which provides optimum torque to the balance is used (the stopworks are essentially a kind of constant force mechanism, intended to provide some of the same advantages as a fusée and chain, but without the significant increase in parts, complexity and cost that using a fusée would incur).

The movement is laid out in a beautifully symmetrical fashion. The center is taken up by the single, very large mainspring barrel, which is secured under its own cock, and which is wound with a key via the square arbor at the center of the barrel. The first wheel in the going train is symmetrical with the balance cock and the whole first impression is a powerful one of leisurely excellence in every detail.

Screws are immaculately finished, and heat blued. The two screws fixing the cock for the first going train wheel, and the balance cock, are symmetrical with each other, as are the larger screws fixing the movement in the case on either side. The glow of the gilt finished brass parts contrasts beautifully with the blued steel, and this color scheme was emulated by George Daniels in his own work, and can be found today in the work of Roger Smith. The various finishes are extremely attractive purely from a decorative standpoint, but they have a practical purpose as well, in that heat bluing, black polishing (as seen on the pare-chute spring and regulator) are all designed to reduce the possibility of corrosion on the brass and steel parts.

A couple of words about the escapement are in order. Breguet used a number of different escapements, including the chronometer detent and lever escapements, as well as some of his own invention. In the Souscription watches, he used the cylinder escapement, which had been invented about a century before, in or around 1695, by Thomas Tompion. The cylinder escapement (and its predecessor, the verge) are what are called frictional rest escapements, thanks to the fact that the escape wheel is in constant contact with the escapement itself.

The cylinder escapement gets its name from the the notched cylinder on the balance staff. In the diagram above, the escape wheel turns clockwise. As the balance rotates anticlockwise, the escape wheel tooth trapped inside the cylinder emerges from the notch and the incline on its tooth presses against the edge of the notch, urging the balance around. (An animation is worth a thousand words).

Generally speaking the cylinder escapement is considered inferior to the lever, as the lever escapement is “detached,” which is to say, it is only in contact with the balance during the brief instant when unlocking and impulse occur. However, the cylinder escapement was essential in the development of flatter watches and takes up much less room than the earlier verge – it was the cylinder escapement that made possible the first generation of ultra-thin watches.

Breguet, also, put his mind to the optimization of the cylinder escapement. As George Daniels notes in The Art Of Breguet, the cylinder escapements created by Breguet in the late 18th and early 19th centuries are head and shoulders above those created by other watchmakers. (In my copy of The Art Of Breguet, this watch is figure 182a-b, with the black and white photo taken by Daniels with his Leica film camera). To reduce friction to a minimum, Breguet used a cylinder made of ruby, and had a number of other features designed to improve its precision. He experimented continually with improvements to the cylinder escapement and by 1795 he had hit upon the configuration he would use for the rest of his life. Daniels writes, “The [cylinder escapements of Breguet] performed so well and with such increased consistency of rate, that temperature errors previously swamped by general bad performance now needed correction. For this reason, except in his smallest watches, Breguet’s ruby cylinder escapements employ a compensation curb.”

He goes on to say, “As developed by Breguet, the ruby cylinder cannot sensibly be improved upon. What had once been an escapement of indifferent performance had been converted by his intuitive understanding of its qualities, into a means of keeping useful time for relatively inexpensive watches. It is used in all souscription watches and in hundreds of repeaters. It will, if properly cleaned and adjusted, keep time to within one minute per day for many years without attention.”

There is so much more that could be said in appreciation of the attention to detail in this watch – the two small cocks for the third wheel and escape wheel, for instance, are filed and polished so that the metal appears to have been somehow folded into shape, like a piece of origami. For an even closer look at the workings of a souscription watch, I highly recommend the disassembly and analysis done over at The Naked Watchmaker.

Using the watch was straightforward. The owner would simply wind up the mainspring with the provided key, and then, set the position of the single hand with the same key (both the movement casebacks and the dial are on hinges, to provide access to the square setting arbors; the hour hand is friction fit on its post). This offered the opportunity for a careless owner to damage the watch – there is a Sherlock Holmes story in which he deduces, after examining a pocket watch which unknown to him was owned by Dr. Watson’s unfortunate brother, that the owner had struggled with alcohol as the innumerable scratches around the hole for winding the mainspring attested to a trembling hand attempting to wind the watch at night.

This particular Breguet, which is now 218 years old and counting, has come down to us in impressively unmarred conditions. There are of course small signs of the passage of time but much less than you might expect and the crisp clarity of the lines of the watch, the engraving, and the high quality of the work still have the power to impress and move us, even after two centuries and more. Honest, untouched condition indeed.

Most of us go through life without ever having a chance to actually handle a Breguet made during his lifetime, and there is in this watch ample evidence of the peerless good taste and faultless excellence in design and execution which made Breguet a legend in his time, and up to the present day. Truly with this watch, one might feel as if one has the brains of a genius in one’s pocket (only less squishy).

After 218 years I should look so good.